📚 The End of an Era: Pima County Library Director Retires as $6.2M Wells Fargo Move Reshapes Downtown Library | Pima BOS 6.3.25

$6.2 million purchase marks end of Joel D. Valdez era while $44M in reserves dwindle to fund preschools

😽 Keepin’ It Simple Summary for Younger Readers

👧🏾✊🏾👦🏾

📚📈 Pima County is making major changes to how libraries work across our region. 🚪👋 The person who has worked for the county library for 34 years is retiring, and at the same time, the main downtown library is moving from its current building to the old Wells Fargo bank building across the street.

🏢🏦 The county has been taking money from the library's savings account—about $10 million every year—to pay for preschool programs that help kids whose families can't afford childcare. 🍼👶 While helping young children is really important, the problem is that the library is running out of money fast.

💸⏳ The county says their plan will work, but their own numbers show the library might only have enough money left for basic operations by 2029. 📅🤔 The move also means some of the library's special collections—old books, maps, and documents about our region's history going back to Native American settlements—might not fit in the new building.

📚🗺️ So residents are facing big changes: a new library building, a new library director, and questions about whether there will be enough money to keep both good library services and preschool programs running in the future. 🤔💭

🗝️ Takeaways

📚 Library Director Amber Mathewson retires after 34 years of service, leaving during an unprecedented transition period

🏢 County purchasing $6.2M Wells Fargo building to replace Joel D. Valdez Main Library across the street

💰 Library reserves dropping from $44.4M to just $1.5M above minimums by 2029 due to $10M annual PEEPs funding

📈 County projects 6%+ property tax growth while Pima Community College estimates a realistic 2% from the same tax base

🏠 If county projections prove accurate, housing costs would rise 24% by 2029, pricing out longtime residents

📜 Specialized collections documenting regional Indigenous heritage and territorial history face an uncertain future

🎒 PEEPs program serves 1,400+ children annually, but the funding model creates long-term sustainability concerns

⚖️ False choice between libraries and early education reflects broader pattern of pitting essential services against each other

The End of an Era: How Pima County's Library Crisis Reflects Deeper Changes in Our Community

I remember going to the Marana library regularly, back when it was just a small one-room operation sharing the building with the sheriff's department.

Qué tiempos aquellos—what times those were!

I remember one afternoon in high school when a whole busload of us—which would never have even fit inside the tiny Marana library—took a field trip to the Main library downtown. We marveled at the vast collections, the specialized archives that document our region's deep history, and the resources that connect us to stories spanning from ancient Hohokam settlements to territorial Arizona.

The Marana library was eventually shuttered by the county, another casualty of budget constraints and shifting priorities. Now, decades later, I'm watching the same pattern unfold downtown, where the Main library—with its irreplaceable special collections—faces an uncertain future as county officials orchestrate what can only be described as institutional change on a massive scale.

As someone who has lived in the borderlands of Southern Arizona for nearly half a century, watching these developments feels like witnessing the slow erosion of the institutions that have anchored our community's memory and identity.

The changes ahead aren't just about budgets and buildings—they represent a fundamental shift in how we preserve and share the stories that make this region unique.

A Perfect Storm: Three Major Changes Converging

What's happening at Pima County isn't just routine government business. Three significant developments are converging to create unprecedented changes in how library services operate across our region, and every resident should be aware of what's to come

The Departure of a Library Institution

After serving Pima County for 34 years, Library Director Amber Mathewson has announced her retirement, with her final day being June 6, 2025. Mathewson began her career here in February 1991, meaning she's overseen the library system through decades of growth, technological change, and community evolution. Her departure during this period of financial uncertainty creates a leadership vacuum at a critical time.

For those of us who have witnessed the library system evolve over the decades, Mathewson's departure signifies the end of an era with significant changes on the horizon.

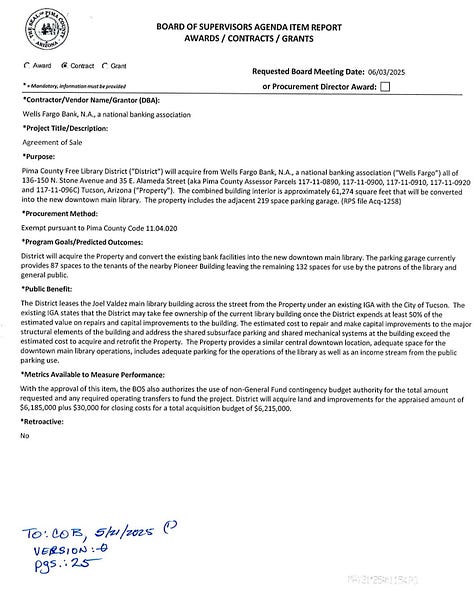

The Wells Fargo Building: A $6.2 Million Solution

The county has committed to purchasing the former Wells Fargo building at 150 N. Stone Avenue for $6.2 million to house the new downtown main library. This isn't a small decision—we're talking about a 61,274-square-foot building that includes a 219-space parking garage, with 132 spaces available to library visitors and the public.

According to reporting by the Arizona Luminaria, what started as discussions about a "temporary space" while the current library underwent repairs has evolved into a permanent relocation. The building, constructed in 1957 by the now-defunct Southern Arizona Bank and Trust, served as Wells Fargo's main branch until it closed in 2023.

For longtime residents who remember when that corner housed one of downtown's most prominent financial institutions, seeing it transform into a library represents both continuity and change—the same kind of adaptive reuse that has characterized downtown Tucson for generations.

The Financial Reality: From Abundance to Scarcity

Perhaps most concerning is the complete transformation of the Library District's financial picture. For years, the district has been a model of fiscal responsibility, consistently spending less than it collected and building healthy reserves. Those days are ending.

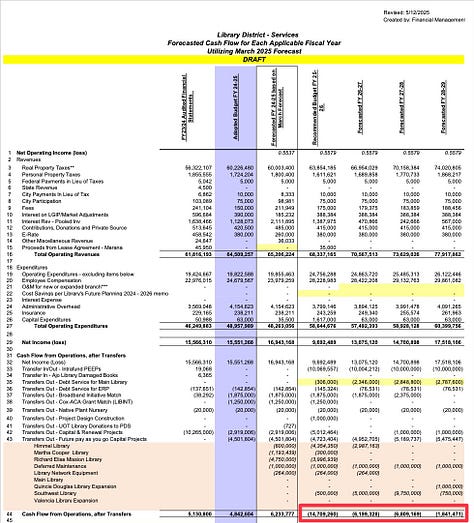

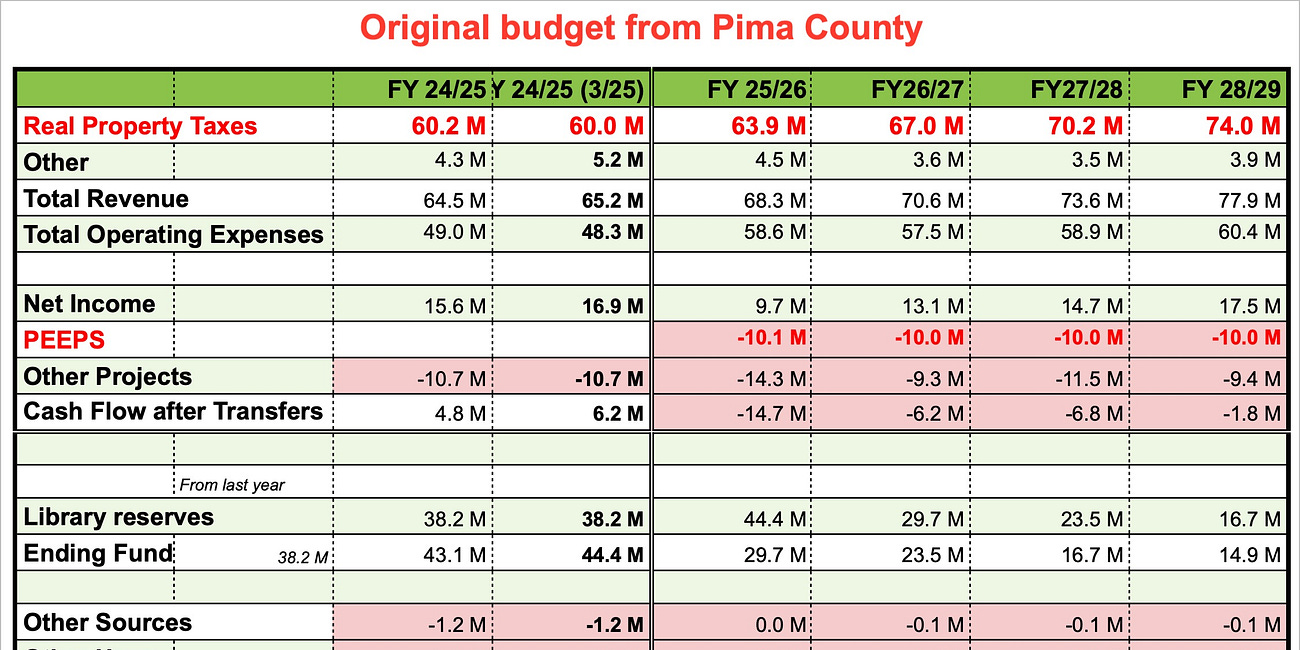

The Pima County Board of Supervisors has already committed to transferring $10 million annually from library reserves to fund the Pima Early Education Program (PEEPs) for the next three years. While early childhood education deserves strong support, the funding mechanism creates serious long-term challenges.

According to financial projections obtained through public records, the Library District's cash reserves will drop dramatically:

FY 2024/25: $44.4 million in reserves

FY 2028/29: Just $1.5 million above required minimums

Every year forward: Negative cash flow

Understanding the Numbers: Why This Matters to You

The county's financial projections rely on assumptions that deserve scrutiny. Officials project property tax revenues will grow from $60 million to $74 million by 2028/29—an annual increase of more than 6%. Yet Pima Community College, which draws from the same property tax base, projects growth of less than 2%.

This isn't just an academic disagreement about spreadsheets. If the county's optimistic projections prove wrong, residents will face difficult choices: reduced library services, higher taxes, or cuts to preschool programs that serve working families.

If the county's projections prove correct, that creates a different problem. Property values rising 6% annually would mean a 24% increase by 2029, pricing many longtime residents out of neighborhoods their families have called home for generations.

What We're Losing: The Special Collections Story

The move to the Wells Fargo building brings practical challenges that go beyond square footage. The current Joel D. Valdez Main Library, built in 1990 on the site of the former Jácome's department store, houses collections that have grown organically over more than three decades.

Elders and historians recall when that corner of Stone Avenue bustled with shoppers from Jácome—seeing the library rise on that historic site felt like a continuation of the area's role as a community gathering place. Now, with another transition ahead, longtime residents wonder what collections and resources will make the journey across the street.

According to the Arizona Luminaria, renovating the current building would cost an estimated $86 million, with $3.5 million needed just for immediate maintenance.

For those of us who value the institutional memory these collections represent, any potential loss of local historical resources represents more than just administrative inconvenience—it's about preserving the documentary threads that connect us to the generations who shaped this desert crossroads.

The PEEPs Program: Good Intentions, Complex Funding

The Pima Early Education Program serves hundreds of children annually and provides crucial support to working families. Nobody questions the value of early childhood education—research consistently shows its long-term benefits for children and communities.

The challenge lies in the funding approach. By drawing $10 million annually from library reserves, the county has created a financial model that financial analysts would recognize as unsustainable. Library reserves were built through years of careful fiscal management, intended to fund library operations and capital improvements, not ongoing programs in other departments.

County Administrator Jan Lesher's May 2025 memo claims this funding approach is "sustainable and appropriate," but the projections suggest otherwise. Making matters more complex, the City of Tucson is reducing its contribution to PEEPs in half in the upcoming budget year, despite the fact that city residents comprise the majority of the families served.

Historical Context: Patterns We've Seen Before

Those of us with long memories in this region recognize patterns in how public institutions change over time. The closure of rural libraries, the consolidation of school districts, the gradual centralization of services—these shifts often begin with reasonable-sounding efficiency arguments and end with communities losing local access to essential services.

The transformation of the Marana library from a small community anchor to closure, followed by the downtown library's relocation and downsizing, reflects broader trends in how governments approach public services. Each change may seem logical to those in charge, but together they represent a fundamental shift away from the distributed, community-centered approach that once characterized our region.

What Comes Next: Questions for the New Director

The person who takes over as library director will inherit significant challenges. Beyond managing the building transition and collection decisions, they'll need to navigate the financial realities that current leadership has created.

The new director will face questions that have no easy answers: How do you maintain service quality while operating with declining resources? Which collections deserve preservation when space is limited? How do you serve communities across a geographically vast county when your financial foundation is shifting?

These aren't just administrative challenges—they're decisions that will shape how future generations access information, connect with their heritage, and build community knowledge.

Community Response: What Residents Can Do

Understanding these changes is the first step toward meaningful engagement. The decisions have been made, but implementation will unfold over months and years, creating opportunities for community input and advocacy.

Stay Informed: Board of Supervisors meetings include public comment periods, allowing residents to voice their concerns and ask questions. The next meeting is Tuesday, June 3rd.

Engage with the Transition: The new library director will need community support and feedback during this transition period. Local library advisory boards provide formal channels for resident input.

Support Alternative Solutions: Advocate for dedicated funding sources for both libraries and early childhood education, rather than forcing them to compete for resources.

Preserve What Matters: Work with historical societies, genealogical groups, and cultural organizations to ensure important collections don't disappear during the transition.

Looking Forward: Lessons from Our Past

This region has survived dramatic changes before—from the end of copper mining's dominance to the transformation of downtown Tucson, from agricultural communities to suburban development. Each transition brought losses and opportunities, and how communities responded made the difference between decline and renewal.

The current library crisis reflects broader questions about what kind of community we want to be. Do we value institutions that preserve and share our collective memory? Are we willing to invest in services that benefit multiple generations? How do we balance competing needs when resources feel scarce?

Our ancestors—whether Indigenous peoples who sustained communities here for millennia, Mexican settlers who built the foundation of modern Tucson, or territorial pioneers who established our first institutions—faced similar choices about community priorities and resource allocation. Their decisions shaped the community we inherited; our decisions will shape what we pass forward.

The Wells Fargo building may become a fine library, and the PEEPs program will continue serving children who need early education opportunities. But the process that got us here—pitting essential services against each other, making long-term commitments based on optimistic projections, and dismantling specialized collections built over decades—deserves careful examination.

As we move forward, the question isn't just whether these changes will work, but whether they reflect the kind of thoughtful stewardship our community deserves. The answer to that question will emerge in the months and years ahead, shaped by how residents choose to engage with these changes and hold leaders accountable for their consequences.

¡Juntos podemos! Together, we can ensure that whatever emerges from this transition serves the diverse communities that call southern Arizona home.

Support Independent Journalism

This type of community-focused reporting takes time and research. Your support enables Three Sonorans to continue covering the stories that affect our daily lives and long-term community wellbeing. Consider subscribing to our Substack to help maintain independent journalism that puts southern Arizona first.

What aspects of this library transition concern you most? How do you think we should balance funding for libraries and early childhood education? Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments below.

Have a scoop or a story you want us to follow up on? Send us a message!

There must be a legal constraint to prevent redeployment of funds from one purpose to another.