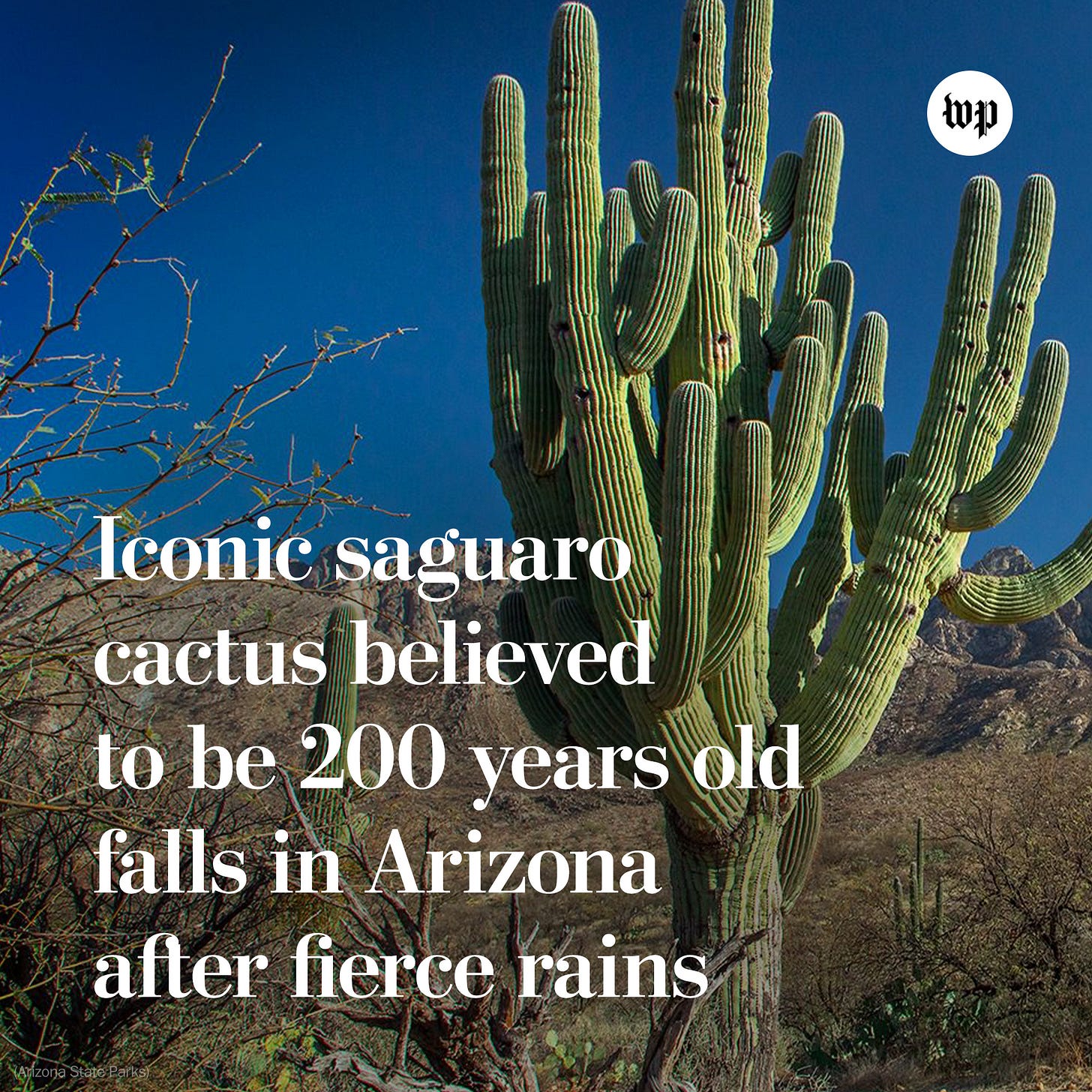

🌵 Saga of a Saguaro: Uncovering the 200-Year Journey of a Legendary Saguaro Cactus

This captivating story reveals the life of a remarkable cactus who lived for over 200 years, witnessing the history of the Southwest.

😽 Keepin’ It Simple Summary for Younger Readers

👧🏾✊🏾👦🏾

A saguaro cactus named "Grandpa" 🌵 lived for over 200 years in the Sonoran Desert 🌞, enduring wars ⚔️, human migrations 🚶♂️🌍, and environmental changes 🌦️. Its story began with a tiny seed 🌱 that sprouted amid historical upheavals, highlighting the resiliency of nature 🌳 despite the shifting landscape of borders 🗺️ and civilizations 🏰. The cactus served as a vital part of its ecosystem 🦉, harboring a variety of wildlife 🐾 while silently witnessing the evolution of its surroundings 🌅. Its eventual fall 🍂 marked not an end but a continuation of life 🌱, as new seeds took root, perpetuating the cycle of existence 🔄 in the desert. 🌵✨

🗝️ Takeaways

🌱 Birth of a Seed: In 1812, a tiny seed landed in the Catalina Mountains, unaware of the historical changes unfolding around it.

🚧 Borders and Wars: As humans drew borders and fought wars, the saguaro continued to thrive, indifferent to such conflicts.

🌊 Ecosystem Champion: Each saguaro cactus supports diverse life, storing water and providing homes for many desert creatures.

🛤️ The Journey of Time: From the Dust Bowl to the Cold War, the saguaro witnessed countless changes, standing strong amid transformations.

🍂 Cycle of Life: When the old saguaro fell, its remains nurtured the soil, giving life to new seeds.

🌵 Roots of Witness: A Saguaro's Unbroken Chronicle of the Southwest

This tale draws inspiration from the true account of a remarkable cactus named "Grandpa," which tragically succumbed to a monsoon storm and was discovered to be over 200 years old!

The First Breath

In the spring of 1812, cannon fire rang out from distant eastern shores as the War of 1812 unfolded. At that time, a tiny seed, no bigger than a grain of pepper, floated into the rugged Catalina Mountains. It arrived through a bird’s droppings and settled among the rocks, its survival dependent on the unpredictable cycles of rain and sun.

The seed established itself in New Spain, later becoming part of Mexico following independence in 1821. This region had vast areas that remained largely uncharted beyond the current borders. The Sonoran Desert functioned as a distinct environment, shaped by the seasons, the movements of Indigenous peoples, and the enduring resilience of its native species.

The seed, unknowing and unburdened, cared nothing for borders or wars. It sought only water, sunlight, and the ancient rhythm of the desert—a language older than memory. If it could think, perhaps it would marvel at the world’s silence, the hum of life carried on the wind, and the promise of roots that would one day anchor it to the earth.

Roots of Resistance

The 19th century brought waves of upheaval to the desert, though the saguaro, still a modest sprout, remained indifferent to the movements of men. In 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ceded vast Mexican territories to the United States, but the land around the young cactus remained firmly Mexican for six more years. The saguaro, still no taller than a boot, grew in quiet defiance of borders drawn by faraway hands.

When the Gadsden Purchase of 1854 brought this land under U.S. control, the desert did not flinch. The cactus did not move—the border moved around it. Buffalo Soldiers soon rode through the arid landscape, their horses’ hooves kicking up clouds of dust that settled on the saguaro’s pleated skin. These Black cavalrymen, many fleeing the brutalities of the post-Civil War South, found a rugged freedom in the Southwest, building roads, guarding settlers, and facing the fierce resistance of Apache warriors.

Cowboys followed, driving cattle across open ranges, their campfires flickering beneath the stars. The saguaro grew slowly, its roots digging deeper. It watched as the desert transformed into a patchwork of fences, trails, and stories told around those fires. It could not understand their words, but it felt their presence—the vibration of hooves, the murmur of laughter, the crackle of flames.

The Biological Symphony

A saguaro is not just a cactus. It is an ecosystem, a living monument to the desert’s delicate balance. Each cactus can store up to 200 gallons of water—1,600 pounds of liquid life. Its pleated skin expands and contracts like a living accordion, breathing with the desert’s rhythm.

By 1900, our saguaro had reached a modest height, its skin scarred by storms and the beaks of woodpeckers carving homes into its flesh. These small hollows became refuges for pygmy owls, who blinked at the world from the safety of its arms. Under moonlight, bats flitted from flower to flower, drinking nectar and carrying pollen across the desert. The saguaro was no mere observer; it was the heartbeat of its ecosystem.

Its first arm appeared around 1905, a slow, deliberate gesture toward the sky. Each arm was a testament to survival, a record of decades endured. By the time humans first flew in airplanes, the cactus stood tall, its arms reaching like a desert choir singing a hymn of patience.

Migrations and Transformations

The Dust Bowl of the 1930s sent waves of migrants streaming west, their overloaded vehicles groaning under the weight of possessions and desperation. Route 66 became a lifeline, carrying families from Oklahoma, Kansas, and Texas near the Sonoran Desert. They passed near the saguaro, their dreams trailing behind them like desert dust.

One family stopped nearby—a battered Ford truck parked beneath the cactus’s growing shadow. A young boy, barefoot and sunburned, wandered toward it. He tilted his head back to take in its height, his eyes wide with wonder. For a moment, he reached out a hand to touch the cactus’s spiny skin before his mother called him back. The saguaro stood still, its arms outstretched, a silent witness to their fleeting moment of hope.

Decades later, as Highway 80 and then Interstate 10, a coast-to-coast freeway, carved through the desert, the landscape shifted again. Asphalt replaced wagon trails, and gas stations sprouted where mesquite once grew. The desert’s pulse quickened, its stillness disrupted by the roar of engines and the glare of headlights. The saguaro, now towering with multiple arms, stood firm, its roots unshaken.

Guardians of a Secret War

The Cold War turned the desert into a hidden fortress.

Titan missile silos, mechanical sentinels of nuclear deterrence, were buried beneath the earth, their presence marked only by the occasional hum of machinery. Just miles from the saguaro, these silos stood ready to unleash destruction unimaginable to the cactus that had only ever known the quiet rhythms of life.

When humans turned their eyes to the moon, the saguaro seemed to stretch a little taller. In the 1960s, nearby Kitt Peak Observatory became a gateway to the stars, its telescopes peering into the same sky the cactus had watched for over a century. The desert, it seemed, was no longer a place to endure but a place to dream.

A Window to Another World: Biosphere 2

In 1991, near the saguaro’s watchful gaze, a massive glass structure rose from the desert floor. Biosphere 2 was humanity’s audacious attempt to recreate entire ecosystems under glass. Eight scientists sealed themselves inside the 3.14-acre facility, testing whether humans could survive in a self-contained environment.

The saguaro might have chuckled if it could, its roots tangled in the very soil humans sought to mimic. For over a century, it had thrived in the delicate balance of the desert’s natural systems. It knew what humans were only beginning to understand: survival requires patience, adaptation, and respect for forces far older than ourselves.

The Desert Surrenders

By the early 2000s, Oro Valley emerged from the desert scrub. Saddlebrooke and Rancho Vistoso—once impossibilities—became sprawling realities. Shopping centers rose where saguaros once stood. The untouched desert that had existed since the Hohokam began to disappear, replaced by the hum of air conditioning and the glow of parking lot lights.

The saguaro, now nearly 200 years old, stood tall amidst the encroachment, its arms raised as if in quiet protest. It had outlived wars, migrations, and revolutions, but it could not outlive the hunger of human ambition.

The Final Chapter

When the monsoon finally claimed the saguaro, it did not fall in vain. Its collapse was not an ending but a transformation. Its woody skeleton became a home for packrats, a nesting ground for woodpeckers, a perch for Harris’s hawks. Its flesh returned to the earth, nourishing the soil for the next generation of life.

Nearby, a tiny seed carried by a bird found purchase in the rocky soil. The cycle began again.

A Desert Meditation

Look closely at the saguaros in the Sonoran Desert. Each is a library, a chronicle, a living history book. They have seen empires rise and fall, wars rage and subside, and civilizations transform the earth beneath their roots.

Our saguaro—born in 1812, witness to wars, revolutions, and human dreams—may be gone, but its story lives on. It is whispered by the wind, written in the roots of every young saguaro that reaches for the endless Arizona sky.

For the desert remembers, even when we forget.

What a beautiful story!