Critical $86 Million Decision for Pima County Libraries: Renovation or Relocation?

Explore how Pima County is debating a major library funding decision affecting accessibility, equity, and community resources amidst a significant leadership change.

😽 Keepin’ It Simple Summary for Younger Readers

👧🏾✊🏾👦🏾

📚 Pima County's libraries are at a crossroads. They’re deciding if they should fix up an old, important library downtown or build new ones in other areas that really need them 🏗️. It's a huge decision because it involves a lot of money, $86 million! 💸 Libraries aren't just about books—they help people vote 🗳️ and need more workers to run smoothly 🤝. There’s also a big change because the director, who's been with the library for 34 years 🕰️, is retiring soon. People are talking about how fair these decisions are for everyone 🌍.

🗝️ Takeaways

📜 Director Retirement: Library Director Amber Mathewson will retire in 2025, marking a significant change in leadership.

💰 $86 Million Decision: The board is deciding whether to renovate or relocate the downtown library, a choice that will impact resource allocation across Pima County.

📈 Funding Allocation Debate: Proposed costs could address other community needs like new libraries and staffing rather than focusing on downtown.

🗳️ Libraries and Voting: Libraries have become vital for voting access, particularly for marginalized and rural communities.

🛠️ Staffing Inequities: Recent data reveals longstanding understaffing in libraries affecting programming and service quality.

Pima County Library Advisory Board Meeting Report: $86 Million Decision Looms as Community Access Hangs in Balance

BREAKING: Library Director Announces Retirement Amid Critical Resource Decisions

In a stunning development that will reshape power dynamics within one of the county's most vital public institutions, Pima County Library Director Amber Mathewson revealed she will retire effective June 7, 2025, after 34 years with the library system, including 8 years as its director.

Her announcement, delivered with visible emotion at Thursday's meeting, comes at a pivotal moment when fundamental questions about resource allocation, community access, and spatial justice are being decided.

"It's been an incredible 34 years starting as a customer service clerk and all positions in between almost," Mathewson told the board, her voice revealing the weight of her decision. "I couldn't have imagined such a lovely career."

This leadership vacuum arrives precisely when the most vulnerable community members need consistent advocacy as the board faces decisions that will determine whether public spaces remain genuinely accessible to all residents—regardless of socioeconomic status, housing situation, or neighborhood—for decades to come.

The $54 Million Question: Downtown Library Renovation Exposes Deep Inequities

The most contentious and revealing discussion centered on whether to renovate the aging Joel D. Valdez Main Library or relocate to a different downtown building—a decision that reveals how public officials navigate competing priorities and which communities ultimately benefit from limited resources.

Marty, Deputy Director of Construction for Pima County, presented the stark financial contrast that has set up what many see as a false choice between maintaining downtown presence and serving other communities:

"The estimate is just an estimate," Marty cautioned in a carefully measured tone that contrasted with the gravity of the numbers displayed. He methodically broke down how the $86 million would be allocated:

Direct construction costs (interior renovation)

Deferred maintenance for exterior and elevators

Soft costs (fees, internal labor)

Furnishings and equipment

Contingency (15-25%)

Escalation (projected over 3-4 years)

The current main library, completed in 1991, is city-owned property with an assessed value of only $20.5 million. This creates a troubling disparity between investment cost and ultimate asset value that would disproportionately benefit downtown property owners while limiting resources for underserved neighborhoods.

When pressed on whether the building is safe, Marty acknowledged that the elevators "aren't dangerous" but are "bleeding" and need replacement—terminology that masks the lived experiences of disabled patrons and staff who depend on reliable vertical transport in the multi-story facility.

Anthony Batchelder, Deputy Director of Finance and Facilities, outlined what the $54 million in savings could alternatively fund—revealing the opportunity costs of maintaining the status quo downtown:

One full year of the library's operating budget (currently $48 million)

A desperately needed new El Pueblo Library to serve the historically underresourced south side ($22 million)

Additional staffing to expand service hours in neighborhoods cut off from access ($1.6 million for 22 FTEs)

$2 million in new materials to address collection gaps

Express library locations for underserved communities currently without walkable access

The body language among board members shifted visibly as these numbers were presented, with some leaning forward intently and others sitting back with arms crossed.

Board member Anna expressed raw frustration about the situation, placing the blame squarely on city officials: "I am very disappointed that the city honestly hasn't lived up to its part of the MOU, which is why we're at the place where we are now. But I just can't see pouring that much money into a facility that is valued at way under what we'd be spending to rehab it. And then the fact that we would never own it."

Another board member Maria pushed back forcefully: "I don't like to see the libraries pitted against each other. And I agree El Pueblo needs a new location. But just because Wells Fargo's window is open, that doesn't make it the right match." Her comments revealed the underlying tension about whether the decision process itself was being rushed to accommodate private market opportunities rather than thoughtful public planning.

The language used by county administrators—particularly the repeated emphasis on "opportunity" rather than "need"—betrayed their preference for relocation despite assertions that no decision had been made.

"If there's an opportunity to do something that's going to meet the needs of this library staff... at a price tag that's much less expensive and makes fiscal sense, that would make sense for us to move forward," one official stated, the conditional tense doing little to mask the predetermined direction.

When pressed on the timeline for community involvement, officials revealed that staff would be consulted first—a concerning reversal of typical engagement practices where broader community input precedes staffing decisions.

The meeting transcript reveals a troubling absence of voices typically served by the downtown library—including unhoused individuals, low-income residents without transportation to other branches, and downtown service workers for whom the library represents a crucial third space. Their perspectives were neither represented on the board nor actively solicited in planning.

Voting Access: Libraries as Democracy's Front Line

In a powerful presentation that illuminated libraries' essential role in protecting democratic participation, County Recorder Gabriella Casares-Kelly and Elections Director Constance Hargrove shared detailed data about how libraries have become critical infrastructure for ensuring marginalized communities can exercise their voting rights.

"We could not execute the election without the use of your voting locations," Casares-Kelly told the board, emphasizing that libraries serve as crucial access points for historically disenfranchised communities.

Casares-Kelly, who introduced herself as being from the communities of the San Xavier District in the Tohono O'odham Nation, explained how geography intersects with voting access: "Rural is in my heart and soul. We have additional challenges out there."

The data presented revealed just how profoundly libraries impact electoral participation:

22,000 early ballots were issued at library locations during the 2024 general election

Oro Valley Library alone served 6,206 voters despite being open for only two weeks

Libraries with the highest turnout were Oro Valley (6,206), Wheeler Taft Abbett (2,300), and Miller-Golf Links (2,100)

Drive-through ballot access at Oro Valley Library mainly served disabled voters, elders, and parents with children

Casares-Kelly connected these numbers to real-world impacts: "Without that, those voters would have been disenfranchised and would not have been eligible to vote," she explained regarding library-based voter registration services that became especially critical after court rulings changed documentation requirements just weeks before the registration deadline.

Hargrove highlighted how libraries' role has evolved dramatically: "Prior to 2022, libraries were used as polling places, but they were not used for training. The impact that libraries have had since I've been here to allow us not to have to pay $1,200 for a location to train poll workers... is huge."

She also noted that the transition to vote centers has increased facilities demands: "With vote centers, voters can vote anywhere just like with early voting. So there is no way to predict how many people will show up."

Both officials expressed deep gratitude for libraries' flexibility and collaboration, acknowledging that hosting voting services disrupts library programming spaces. Their testimony revealed how public institutions can work together to strengthen democratic participation—a stark contrast to the competitive resource allocation framework evident in the main library discussion.

Staff Inequities Unveiled: New Data Tool Exposes Years of Understaffing

Deputy Director Em DeMeester-Lane, who recently completed his first three months in his role after 17 years with the system, presented a data-driven approach to library staffing that has finally quantified what frontline staff have reported for years: dramatic understaffing that has limited programming capacity in the communities that need it most.

"When we think about staffing, I really want to think about all the things that have to be done outside of just checking books out," he explained, detailing how he's implemented standardized scheduling ratios that quantify service points across libraries—allowing for the first time an objective measure of staff allocation equity across the system.

DeMeester-Lane described spending late summer in what he called his "Beautiful Mind era," developing complex formulas and creating a whiteboard covered with equations to quantify workload. "It's been frustrating my whole career," he acknowledged, validating longstanding staff concerns about workload inequities.

The new system classifies staffing ratios into tiers with real-world implications for service quality:

3-5 ratio: "Thumbs up, you're doing awesome" (fully staffed)

5-6 ratio: "Sustainable for about two days" (minimal coverage)

6-6.9 ratio: "Getting murky on meeting coverage" (one-day emergency only)

7+ ratio: "We need to send help" (requires immediate intervention)

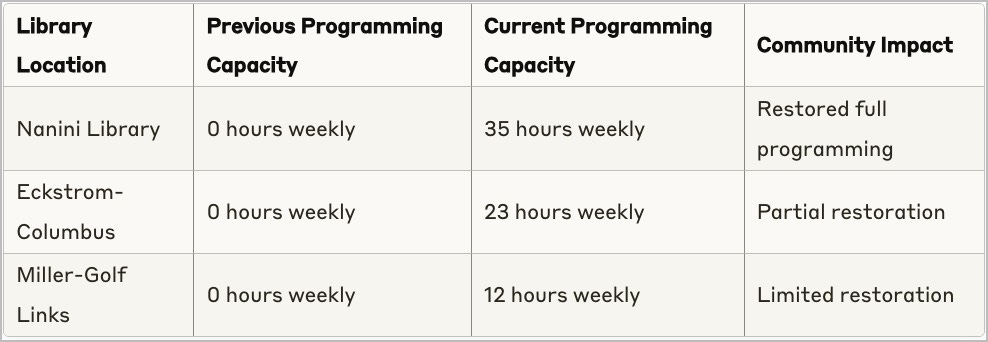

Most remarkably, DeMeester-Lane demonstrated how recent staffing improvements have begun addressing programming inequities that have limited access in high-impact communities:

The data revealed that some branches had been attempting to offer programming despite having zero capacity—placing unsustainable burdens on staff and limiting quality. This invisible labor, performed disproportionately by lower-paid staff without management titles, had gone unquantified and unacknowledged until this initiative.

DeMeester-Lane connected these metrics to real-world access concerns: "Our community—the workers in our community—need to be able to access the library at times when they're available," he emphasized, hinting at potential Sunday hours expansion.

His statement acknowledged the reality that current library hours primarily serve those with traditional weekday schedules and flexible transportation options—excluding many shift workers, service industry employees, and those dependent on limited weekend public transit.

Board member Maria praised the approach with visible enthusiasm: "It's fantastic that you are quantifying everything. It's probably very gratifying to the librarians who do programming to see that acknowledged in a quantitative way."

The staffing tool presentation represented a rare moment of near-unanimous support among board members, suggesting potential for data-driven advocacy that could leverage quantifiable metrics to secure additional resources for chronically underfunded branches.

However, it also underscored the painful reality that some communities have endured years of limited access due to understaffing—an inequality that remains unaddressed in current budget allocations.

Community Engagement: Promises vs. Historical Practice

The meeting also featured a presentation from Marty detailing the county's approach to community engagement for library renovation projects, using the Himmel Park Library expansion as a case study.

The process supposedly includes:

Identifying stakeholders (community groups, neighbors, staff)

Developing outreach plans

Multiple public meetings

Digital communication and printed materials

Focus groups with specific communities

Tours and site visits

However, his presentation's emphasis on the Himmel Park process—a relatively wealthy neighborhood with high civic engagement—stood in stark contrast to the rushed timeline presented for the downtown Main Library decision, raising questions about whether all communities receive equal engagement opportunities.

Several board members expressed explicit concern about the potential for rushed decision-making regarding the downtown library, with one directly asking: "How do we set it up so that people have something to be extremely excited about? I think that starts with talking to the staff and getting a solid idea of the needs there and what they see for improvement."

This concern echoed previous community backlash when preliminary library closures were floated without adequate public input. This pattern threatens to repeat if the Wells Fargo building opportunity drives decision timelines rather than a genuine community process.

Votes Taken: Procedural Actions Amid Substantive Questions

Approval of Minutes: The board unanimously approved the minutes from February 6, 2025, with one correction noting that Maria had met with Supervisor Scott rather than board member John. (Vote: Unanimous approval)

Vice Chair Election: John was nominated and unanimously elected as the new Vice Chair, replacing Rebecca Peralta, who had resigned along with board member Craig. No alternative candidates were proposed, and little discussion preceded the vote. (Vote: Unanimous approval)

Adjournment: The meeting was adjourned following a motion by Maria, seconded by John, with unanimous approval. (Vote: Unanimous approval)

The votes themselves revealed little controversy but underscored the advisory board's limited decision-making authority on the substantive issues discussed—particularly the main library's future, which county administrators and supervisors will ultimately decide.

Friends, Foundation, and Funding Realities

The meeting highlighted the increasing dependence on private funding sources to maintain essential library services:

Friends of the Library: Penny reported that the Friends delivered $65,000 to the library from sales proceeds last month and anticipate at least two more equal or greater payments this fiscal year. "We delivered the requested $65,000 last month to the library from the proceeds of our sales," she stated matter-of-factly, revealing how public services now rely on volunteer-driven fundraising.

Pima Library Foundation: Melinda G. McDaniel reported that the Foundation is on target to fund 15 Career Online High School scholarships and 25 mobile hotspots—educational opportunities and digital access that would presumably be covered by public funding in a fully-resourced system.

These reports highlighted the growing privatization of public library funding, with essential services increasingly dependent on volunteer labor and private donations rather than stable tax funding.

This shift has troubling implications for sustained equity, as philanthropic interests may not align with community needs, and volunteer capacity varies widely between affluent and working-class communities.

Breaking the Silence: A Call for Community Mobilization

As Pima County's library system stands at this crossroads, community silence equals complicity in decisions that will determine who has access to information, technology, and public space for decades to come. The potential relocation of the downtown library, strategic expansion of hours, and upcoming leadership transition demand not just polite input but organized community power.

The library's survey remains open through March 17, offering one channel for community voice: This survey will help shape the future of your library! However, survey input alone—which disproportionately reflects the perspectives of those with digital access, time, and English fluency—cannot substitute for robust, in-person organizing that centers the voices of those most dependent on library services.

With multiple renovation projects pending (including Valencia, Bear Canyon, Abbett, and Himmel Park libraries), communities must demand participatory design processes that prioritize the needs of the most marginalized users rather than the most vocal or politically connected stakeholders.

How can we build collective power?

Form neighborhood library advocacy groups with an explicit focus on equity

Organize community testimony for upcoming board meetings

Demand transparent decision-making processes with meaningful timelines for input

Meet with County Supervisors directly to advocate for expanded library funding

Build coalitions between library users, staff, and allied community organizations

What experiences have you had with library access in historically underserved neighborhoods? How would you ensure the voices of unhoused individuals, immigrants, and working families are centered in the Main Library relocation decision? Leave your comments below.

This is a lot to unpack.

I've gone to the Murphy Wilmot library for years, frequently check out books and heavily use the computers and printers.

I'm not sure the surveys will provide representative input to the process.

Almost by accident, I saw the little note about the survey at Wilmot. No one pointed it out or encouraged me to participate in the survey. The staff is always very busy!

There were only a few of the survey notes. I didn't see other people picking them up or paying any attention to the notes about the surveys.