🎨 Murals, Memory, and Movimiento: Why a Tucson Park Name Change Matters More Than You Think

Nextdoor erupts as community weighs honoring 1970s activist against preserving Robin Hood of the West legacy

😽 Keepin’ It Simple Summary for Younger Readers

👧🏾✊🏾👦🏾

A park in Tucson 🌵 is causing arguments ⚡ because some people want to change its name 🏷️ to honor the real person who helped create it 🙌.

The park exists because in 1970 📅, a group of Chicano activists ✊🏽 led by Salomón Baldenegro protested at a fancy golf course ⛳✨ to demand their poor neighborhood 🏚️ get a park too 🌳.

But the current mayor, Regina Romero 🏛️, has spent years making secret deals 🤐💼 with big companies 🏢 and even tried to sell the golf course space ⛳➡️🎓 to a private college without telling the community 🗣️.

Now most people commenting online 💻📱 don’t want to change the park’s name, partly because they don’t trust politicians 🧑💼🤔 who make secret deals 🤝🕶️.

This story shows how communities 👥🏘️ have to keep fighting 🥊🔥 to protect spaces they’ve already won 🏞️✊.

¿Cómo Está la Resistencia? The Battle for Memory and Space at Joaquín Murrieta Park

🗝️ Takeaways

🏆 Joaquín Murrieta Park was born from the 1970s Chicano resistance when activists occupied the El Rio Golf Course, demanding community spaces

💰 Recent $14+ million renovations included a new mural celebrating Chicano culture, sparking additional cultural tensions beyond naming debates

🎨 New mural by Alfonso Chavez celebrating community struggle faces criticism as "too political" from some residents

⚖️ Regina Romero's decade-long pattern of corporate secrecy—from Grand Canyon University to Project Blue—shows continuing threats to community control

👩⚖️ El Rio Coalition II, led by Salomón's wife Cecilia Cruz-Baldenegro, successfully fought Romero's secret attempt to sell El Rio to Grand Canyon University

🌊 Trump Era context amplifies debates about cultural preservation as attacks on Chicano communities intensify nationwide

🏢 If Romero had succeeded in giving El Rio to Grand Canyon University, there might not be a park to rename today

Quotes:

Salomón Baldenegro: "We had come to realize that they [Tucson Democrats] had taken advantage of us and taken us for granted. We said we wanted a park." - On 1970s political betrayal

Salomón Baldenegro (on Grand Canyon University deal): "highlighted the contempt Mayor Jonathan Rothschild and council members Regina Romero... have for the westside" - In Tucson Weekly

Alfonso Chavez (Muralist): "It's a mural for Joaquin Murrieta Park here celebrating the community and all that has been fought for, for us to exist in such a beautiful space." - Defending Chicano cultural art

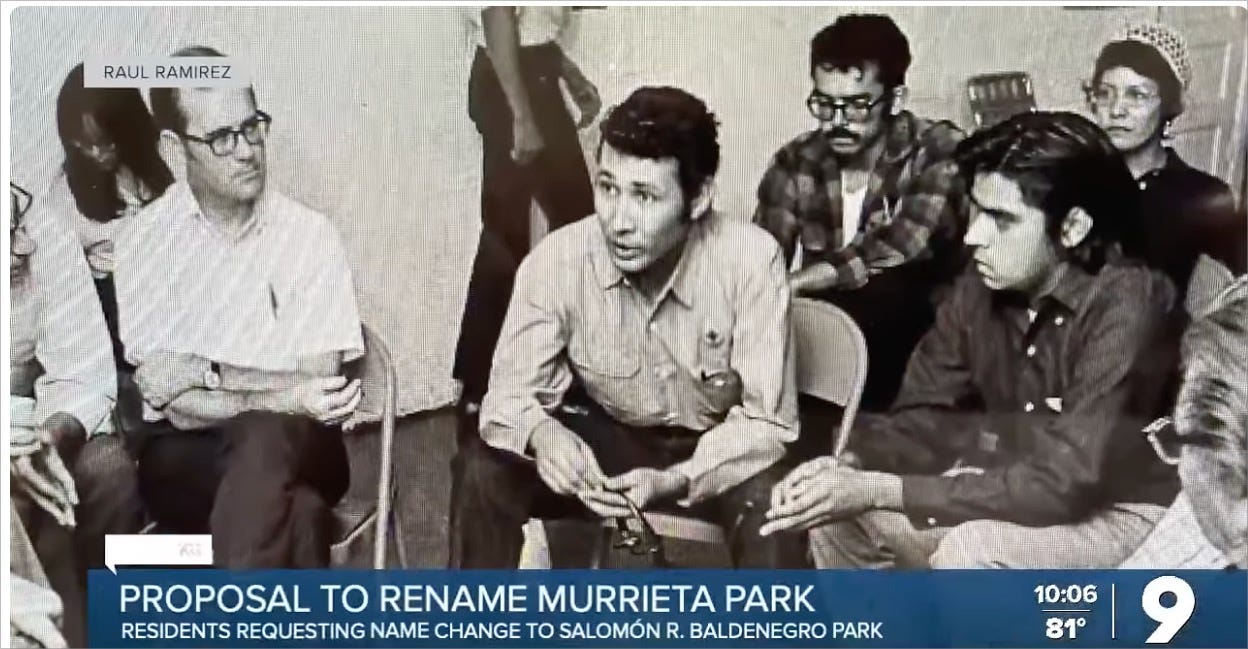

Raul Ramirez (Renaming Advocate): "Many of us consider him as the father of the Chicano movement in Tucson because he was involved in this protest movement that resulted in benefits for the whole community." - Supporting Baldenegro naming

Attorney Bill Risner (on Grand Canyon University deal): "It was an extreme, extraordinary, phenomenally corrupt deal from the bottom to the top, which any person who looked at that deal would be totally amazed." - On Romero's secret negotiations

Sip that café con leche and settle in, raza, because we've got a story that cuts straight to the corazón of who gets remembered in our community spaces—and who's been fighting to erase our organizing legacy for over a decade.

The dusty trails of Tucson's west side are once again echoing with the sounds of struggle, this time over the proposed renaming of Joaquín Murrieta Park to honor Salomón R. Baldenegro.

But this isn't just about swapping out a metal sign, hermanos y hermanas. This is the latest chapter in a much longer war between corporate-friendly politicians and the comunidad that refuses to let their stories be buried.

The Sacred Ground: Where Resistance Was Born

To understand why this naming controversy matters—why your abuela's stories matter, why your children's playground politics matter—we need to travel back to 1970, when the west side looked nothing like the renovated spaces families enjoy today.

Picture this: Barrio Hollywood, separated from the lush El Rio Golf Course by nothing more than Speedway Boulevard, but divided by an ocean of neglect and institutional racism.

According to the Tucson Weekly, the barrio had "unpaved roads and no sidewalks," and many residents relied on outhouses because the city couldn't be bothered to extend sewer service to la gente.

Meanwhile, white golfers putted across manicured greens just yards away, protected by fences that city officials claimed were for "safety" but residents understood as barriers of exclusion.

Because nothing says "public service" like ensuring your golf game isn't interrupted by the sight of poverty, ¿verdad?

Salomón Baldenegro, then a young Chicano activist, watched his neighbors navigate dirt roads while city council members made empty promises. As he told the Arizona Memory Project, Democratic candidates had promised the community a park in exchange for votes in the 1967 election.

Three years later? The politicians had their victories, and the west side had their dirt roads. "We had come to realize that they had taken advantage of us and taken us for granted. We said we wanted a park."

August 15, 1970: El Día Que Todo Cambió

Sometimes resistance isn't planned in boardrooms or announced in press releases. Sometimes it erupts from the heart of a comunidad that has had enough.

On that August day in 1970, over 200 protesters—led by Baldenegro and a grandmother named Sacramento Rodríguez—marched onto El Rio Golf Course and disrupted play.

According to Inside Tucson Business, "Baldenegro was among organizers who brought more than 200 people out to occupy the course and disrupt golf play." Among those young activists was future Congressman Raúl Grijalva, who would carry the lessons of that day throughout his political career.

Imagine the audacity—brown bodies walking across spaces designed to exclude them, demanding not charity but justice. The nerve of people thinking they deserved what their tax dollars funded.

The occupation worked. After negotiations, the city agreed to carve out space for both the El Rio Community Center and what would become Northwest Park—later renamed Joaquín Murrieta Park in 1990.

The Murrieta Legacy: Mythology Meets Movement

The choice of Joaquín Murrieta's name wasn't accidental. According to KGUN 9, Murrieta was "called Robin Hood of the West during the Gold Rush in California when Anglo settlers took over properties and power, often by force from the Spanish and Mexican residents."

The legendary figure represented resistance against Anglo colonization—exactly what the Movimiento Chicano embodied in demanding community spaces. By choosing his name, residents connected their local struggle to broader narratives of Chicano resistance across the Southwest.

Regina Romero's War on West Side Organizing: The Pattern Emerges

Here's where our story takes a darker turn, because the current naming controversy can't be understood without recognizing a disturbing pattern: Regina Romero's decade-long hostility toward the very community organizing that created the space she now oversees.

Around 2010, when corporate interests again tried to devour El Rio, Cecilia Cruz-Baldenegro—Salomón's wife—reformed the El Rio Coalition II to fight another battle for community control.

The target this time? According to the Arizona Daily Star, the coalition formed "in opposition to a city proposal to help Grand Canyon University build a new campus on the site of the El Rio Golf Course."

Yes, that's right—the same corporate Christian university that bans same-sex couples was going to get handed the space that generations fought to keep public.

And guess who was pushing this backroom deal? Regina Romero, then Ward 1 councilwoman.

According to the Tucson Weekly, Salomón Baldenegro himself wrote that the GCU debacle "highlighted the contempt Mayor Jonathan Rothschild and council members Regina Romero, Paul Cunningham, Karin Uhlich, and Shirley Scott have for the westside—only council members Richard Fimbres and Steve Kozachik stood with the westside."

Because nothing says "community representation" like secretly negotiating to hand sacred resistance space to a homophobic corporation, ¿verdad?

When community activists requested public records about these secretive negotiations, something muy conveniente happened. As reported, "suddenly her office computer was stolen... without the alarms being tripped or any evidence of a break-in.”

In the end, the community activists defeated Regina Romero’s corporate desires once again.

Sound familiar? It's the same pattern that would repeat years later during the Project Blue controversy, when Romero again supported a massive corporate water grab until community pressure forced her to back down.

The Redistricting Retaliation: Dividing to Conquer

However, Romero's attacks on West Side organizing and specifically El Rio didn't stop with corporate giveaways.

In 2021, according to Fronteras Desk, when redistricting threatened to split up Ward 1's historically Chicano communities, Romero's opposition wasn't about preserving community integrity—it was about maintaining her political control.

The redistricting proposal would have "split the University of Arizona and the Fourth Avenue restaurant and retail district from the city's downtown" and potentially diluted Latino voting strength. But notably absent from Romero's public complaints was any mention of how the proposed changes might affect the Barrio Hollywood, El Rio, and other west side communities that had been the backbone of Chicano organizing for decades.

¿Casualidad? Coincidence? I think not. When you've spent years trying to undermine West Side organizing, why wouldn't you want to split up their voting power?

According to the Tucson Sentinel, Ward 1 "stretches from downtown's El Presidio and Dunbar/Spring neighborhoods to the city's western border and from the Sombras del Cerro neighborhood on the north side to Midvale Park and Barrio Nopal on the South Side."

This geographic diversity requires representatives who understand both gentrifying downtown areas and historically disinvested barrios—exactly the kind of coalition-building that effective community organizing creates.

2025: Renovación y Revolución Cultural

Fast-forward to today, and Joaquín Murrieta Park has undergone a stunning transformation.

According to Tucson Delivers, the city invested over $14 million from Proposition 407 bonds to create new baseball fields with lights, a splash pad, modern playgrounds, and over 100 new trees.

But the most culturally significant addition is the new mural by local artist Alfonso Chavez. As he told KGUN 9, "It's a mural for Joaquin Murrieta Park here celebrating the community and all that has been fought for, for us to exist in such a beautiful space."

This mural isn't decoration—it's declaration. A visual reminder that this space exists because people fought for it, not because city officials felt generous. And predictably, several community members have criticized it as "too political"—because apparently, acknowledging Chicano resistance makes some people uncomfortable.

The Naming Controversy: The Final Insult?

Now comes the proposal to rename the park after Salomón R. Baldenegro himself. According to KOLD News, the city has opened a 45-day public comment period through October 17, 2025.

Raul Ramirez, leading the renaming effort, argues that "many of us consider him as the father of Chicano movement in Tucson because he was involved in this protest movement that resulted in benefits for the whole community."

But here's the thing that makes this controversy so painful: if Regina Romero had succeeded in her Grand Canyon University scheme, there might not be a park to rename today. The green space that families now enjoy, the fields where kids play baseball, the splash pad where children cool off in our brutal desert heat—all of it could have been lost to corporate development.

¿Y ahora qué? And now what? Now that the community successfully defended this space AGAIN, we're supposed to trust the same mayor who tried to give it away to decide whether its original organizer deserves recognition?

Nextdoor Speaks: Las Voces del Pueblo

Our analysis of over 120 Nextdoor comments reveals a community landscape that should concern anyone who cares about justicia: 71.5% oppose the rename, 5.7% support it, and 22% remain neutral. But the reasons for opposition expose deeper currents of resistance to Chicano memory and cultural recognition.

The most common concerns include cost objections ("$10,000 fiasco"), preferences for building new facilities rather than renaming, and troubling personal attacks on Baldenegro's character from decades past. One commenter claimed he "put down anyone who was not Hispanic in a big way" during a high school presentation. Claims of “reverse racism” are common now during the Trump Era.

Interesting how suddenly everyone has budget concerns about honoring Chicano organizers, but nobody complained when millions were being secretly negotiated away to corporations.

What's most revealing is the geographic pattern: many opposing voices appear to be longtime residents from adjacent neighborhoods rather than families from the historically Chicano communities most directly served by the park.

This raises crucial questions about democratic participation—should naming decisions affecting historically Chicano spaces be determined by broader Tucson residents, or should they center the voices of communities most connected to the space's origin story?

The Real Stakes: Corporate Memory vs. Community Truth

This controversy reveals something deeper than park naming politics. It's about whether communities get to control their own narratives or whether corporate-friendly politicians can erase inconvenient histories of resistance.

Think about the timeline: Regina Romero spent years trying to undermine the very organizing legacy that created this space. She supported giving El Rio to Grand Canyon University. She backed Project Blue until community pressure forced retreat. She's shown consistent hostility toward West Side activists who demand transparency and community control.

¿Y ahora qué nos quiere hacer creer? And now she wants us to believe what?

The mural controversy exemplifies this tension. Several Nextdoor commenters criticized Chavez's artwork as "uninviting" and too political, demanding "something of the nature of the area" instead of what they perceived as partisan messaging.

Translation: "We want pretty pictures of cacti, not reminders that brown people organized for their rights."

Trump Era Context: Memory as Battleground

These dynamics aren't happening in a vacuum.

As we navigate Trump's second presidency, attacks on comunidades Chicanas and immigrant families have intensified nationwide. In this context, fights over park naming become proxies for broader anxieties about demographic change and cultural belonging.

When corporations get years to plan their schemes while communities get weeks to respond, when politicians can hide behind NDAs and secret negotiations while demanding "civil discourse" from activists, when community art gets criticized as "too political"—the pattern is clear.

Dominant culture tolerates cultura as decoration but resists it as empowerment.

Environmental Justice and Water Security: The Deeper Connections

Behind all this lies a fundamental question about environmental justice and water security in the Southwest. The same mayor who secretly planned to hand massive quantities of precious desert water to Amazon's Project Blue now presides over a decision about honoring the activist who fought to create public green space.

The Colorado River is at historically low levels. Climate change is making our region hotter and drier. This is precisely the time when we need transparent, community-centered decision-making about both water allocation and public space preservation.

¿Dónde está la justicia ambiental? Where's the environmental justice in that equation?

Beyond Binary Thinking: Creative Solutions

The either/or framing misses opportunities for solutions that honor both symbolic and lived resistance. Community member Eugenia L. suggested "Baldenegro-Murrieta Park," acknowledging both the mythological and historical resistance the space represents.

Others proposed dedicating specific facilities—such as the community center or particular fields—to Baldenegro, while maintaining the park's overall name. These approaches recognize that memory isn't a zero-sum game; we can honor multiple generations of struggle simultaneously.

What This Means for You: The Personal is Political

Whether you live in Tucson or thousands of miles away, this controversy affects your community. The dynamics playing out around Joaquín Murrieta Park—corporate capture, cultural erasure, democratic participation—are happening everywhere la raza calls home.

If you're a parent, these fights determine what stories your children learn about resistance and community organizing. If you're an activist, they reveal how cultural memory either supports or undermines current organizing efforts. If you're simply someone who believes communities should control their own narratives, these battles matter deeply.

La Lucha Continúa: Moving Forward with Purpose

As the October 17 comment deadline approaches, this controversy presents an opportunity for a deeper community dialogue about memory, power, and resistance. Rather than choosing between names, la comunidad could use this moment to educate neighbors about West Side history and ongoing struggles against corporate capture.

The renovated park—with its new facilities, mural, and community programming—creates spaces for intergenerational dialogue about resistance, from Murrieta's 1850s rebellion to the 1970 protests to today's fights against displacement and corporate giveaways.

Whether the park keeps its current name or gains a new one, the deeper work remains: building power, preserving culture, and creating spaces where nuestras familias can thrive. The teenagers playing baseball under those new lights, the families gathering at the splash pad, and community members viewing the mural are inheriting both victories and responsibilities.

But let's be clear about something: if Regina Romero truly wants to honor Salomón Baldenegro's legacy, she could start by embracing the transparency and community accountability he fought for, instead of the corporate secrecy and backroom dealing that have defined her tenure.

Porque la memoria es resistencia, y la resistencia es esperanza.

Join the Resistance Through Information: Stay informed about these crucial community debates by supporting Three Sonorans Substack, your source for borderland politics and Indigenous Chicano perspectives that mainstream media ignores.

Get Involved: Submit comments to the City of Tucson through October 17. Attend city council meetings. Engage neighbors in conversations about memory and community values. Most importantly, support local Chicano artists and cultural workers preserving our stories.

¿Qué Piensas? What Do You Think?

Leave a comment below with these questions:

How can communities better balance honoring mythological figures versus real organizers in public spaces?

And what role should demographic proximity play in cultural memory decisions—should historically Chicano spaces be primarily shaped by Chicano voices, or do all residents have equal say regardless of connection to the origin story?

Seguimos en la lucha, siempre adelante.

Have a scoop or a story you want us to follow up on? Send us a message!

I submitted a comment to the City, to wit:

Absolutely I support the name change - why wouldn’t I? People of the west side have fought longer and harder than anyone for basic amenities and to have a say in how they want their neighborhoods developed. Why is this even up to contention by outside commenters?