🗞️ Media Justice in Indigenous Communities: Building a Nation's Newspaper

How grassroots journalism is filling crucial information gaps in Tohono O'odham Nation

Based on the Morning Voice for 5/5/25, a daily radio show in Tucson, AZ, on KVOI-AM. Analysis and opinions are my own.

😽 Keepin’ It Simple Summary for Younger Readers

👧🏾✊🏾👦🏾

The Morning Voice radio show had two interesting guests! 🎙️✨ First was Trinity Norris, a Native American journalist from the Tohono O'odham Nation. She’s working to create a newspaper for her community 📰🌵 and tells stories that highlight the positive things Native people are doing instead of just the problems. 🙌🏽❤️

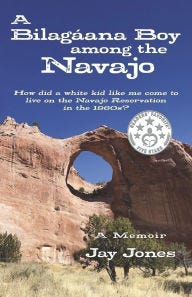

The second guest was Jay Jones, a white man who wrote a book about living on the Navajo reservation as a kid. 📚🏜️ He sometimes felt uncomfortable because he was different from everyone else. 😕

The show helps us understand why it's important for Native people to tell their own stories instead of having others tell stories about them. 📖💬✨

🗝️ Takeaways

🌟 Trinity Norris exemplifies Indigenous media sovereignty by creating journalism platforms that center Native voices rather than explaining them for white audiences

🌍 The Indigenous Resilience Center (IREZ) at U of A operates on the principle that tribal communities already have solutions to environmental challenges—they need resources to implement them

📰 There is currently no functioning newspaper for the Tohono O'odham Nation, highlighting the critical gaps in information access for Indigenous communities

🏆 Indigenous storytellers often face structural barriers in mainstream publishing and media, while white perspectives on Indigenous experiences receive disproportionate attention

🔄 Decolonizing media requires both Indigenous-led platforms and critical examination of which stories receive funding, publication, and amplification

🗣️ Supporting Indigenous journalism through subscriptions, funding, and attention represents a concrete step toward media justice and decolonization

Indigenous Voices Rising: Confronting Colonial Narratives on Morning Voice

In a cultural landscape where Cinco de Mayo has been reduced to margarita specials and sombreros in bar windows across Tucson, Monday's Morning Voice show on KVOI offered something far more substantial—a glimpse into the ongoing struggle between authentic Indigenous storytelling and the persistent shadow of settler colonialism.

As I settled in to listen to the May 5th broadcast, what unfolded was a masterclass in contrasting narratives: one representing Indigenous resilience and reclamation, the other embodying the ever-present white gaze that continues to frame Native experience through settler perspectives.

And isn't that just the perfect metaphor for Arizona itself? A state built on stolen O'odham and Apache land, where the voices that should matter most are routinely drowned out by those who arrived yesterday but speak as if they've always belonged.

Trinity Norris: Decolonizing Journalism One Story at a Time

The first hour featured Trinity Norris, a dynamic Indigenous journalist whose very presence in media spaces represents an act of resistance. As a graduate student at the University of Arizona pursuing her master's in global media (after completing her bachelor's in digital journalism), Trinity isn't merely studying media—she's actively transforming it.

"I think for me, it really comes down to just being able to share stories," Trinity explained with the quiet confidence of someone who understands exactly what's at stake. "I just feel really grateful that people even want me to tell their stories, right? They feel comfortable enough for me to share their stories. They trust me enough."

Trust is sacred, especially in communities where it has been repeatedly violated by extractive journalism that treats Indigenous people as subjects rather than agents of their own narratives. As a member of the Tohono O'odham Nation who grew up in Sells, Trinity brings an insider's perspective to her work with Tucson Spotlight and as the marketing communications graduate assistant at the U of A's Indigenous Resilience Center (IRES).

The Indigenous Resilience Center itself embodies a decolonial approach to environmental challenges. As Trinity explained, "We know that tribal communities already have solutions for their own environmental challenges that they may be facing. And a lot of the time, financial needs are the setback."

Imagine that—Indigenous communities already having solutions to problems created largely by settler colonial capitalism, only to be blocked by the same economic systems designed to keep them dependent. The audacity of resilience in the face of such calculated suppression is nothing short of revolutionary.

Trinity's work extends beyond campus. Her recent participation at the Planet Forward Environmental Journalism Conference in Washington, D.C., where she delivered the opening reflection, placed Indigenous environmental knowledge at the center of national discourse. She highlighted cultural practices like controlled burns, traditional ecological knowledge that Western science dismissed for centuries before "discovering" its effectiveness in recent decades.

"I think it was important to highlight the fact that it's important that we're talking about our stories like this," Trinity said of her keynote, "because a lot of what the planet forward correspondence and what the whole thing was about was environmental storytelling and highlighting different stories or challenges that different places might be facing."

Perhaps most impressive is Trinity's capstone project for her master's degree—creating a newsletter for the Tohono O'odham Nation that could eventually develop into a full newspaper. This isn't just academic work; it's cultural reclamation and community building.

"On the nation, we actually don't have a running newspaper at all," she explained. "It would be very beneficial for our community to have that again, because we did have a newspaper but has since been retired...And so I'm working my way to building that out and hopefully regenerating or reviving a newspaper of the sort."

This project exemplifies what Indigenous media sovereignty looks like in practice—creating platforms where Native voices can speak directly to their communities without external filters, without having to explain or translate their experiences for white audiences.

When was the last time mainstream media dedicated resources to community journalism on reservations? They'll parachute in for poverty porn or casino controversies, but sustained coverage of Indigenous community life and governance? Don't hold your breath.

Jay Jones: The Billagáana Looking In

The second hour featured Jay Jones, author of the newly released memoir "A Billagáana Boy Among the Navajo." The title itself uses the Navajo term for white person/outsider—a linguistic choice that at least acknowledges the perspective from which this story is experienced.

Jones' story begins with personal disruption—his parents' divorce, his mother's remarriage to someone working for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (an organization with a deeply problematic history of enforcing federal control over Indigenous nations), and his subsequent relocation from comfortable Alexandria, Virginia to Window Rock, Arizona in 1967.

"I didn't want to go," Jones admitted. "I had been living, as I said, with my father and Alexandria for two years. And we had a very, very comfortable lifestyle... to have to go to the reservation was not something I wanted to do."

Uncomfortable being moved from your home? Ask any Indigenous elder about boarding schools or forced relocations. Perspective matters.

Jones described his culture shock upon attending the Intertribal Ceremony in Gallup: "It was unbelievable to see when we drove there that particular day... there were Indigenous people coming from all over the place, walking, riding in wagons. A few had cars, but most were walking, riding horses, and they were in wagons. And it's like, is this 1967 or 1867?"

This comment, likely unintentional in its coloniality, reveals the persistent framework that places Indigenous peoples in a distant, primitive past rather than recognizing their living, evolving cultures. The implication that seeing Indigenous people practicing traditional ways in 1967 somehow transported him back in time reinforces the harmful narrative that authentic Indigeneity belongs to history, not the present.

To Jones' credit, he acknowledged how these experiences challenged his preconceptions: "It broke the stereotype of Native American people and really opened my eyes. They were very, very proud in the dance that they were doing and marching in the parade and just showing off their ethnic culture."

"Showing off their ethnic culture"—as if the ceremonies and practices of sovereign nations with histories spanning thousands of years on this continent were mere exhibitions for the edification of white observers. The language of discovery and observation runs deep in settler consciousness.

Perhaps the most revealing anecdote came when Jones described watching Western movies during a sleepover with his Navajo friend Robbie Hubbard: "Here I am, you know, I'm here with these Native Americans, these Navajos, watching them get annihilated. And I had this terrible, terrible, uncomfortable feeling come over me. And Joe [Robbie's brother] said, well, that's the way they always depict us."

Jones continued: "Robbie didn't really care because they had become so used to seeing it. And it's very unfortunate, you know, that it took place because, you know, the way white people ostracize and demonize the Native American, not just the Navajo, but all over reservations throughout the country."

"Robbie didn't really care"—or perhaps Robbie was simply tired of performing his trauma for white comfort. Perhaps in his own home, watching TV with a friend, he chose not to educate a white child about the violence of representation. Perhaps navigating white people's discomfort with their own history was the last thing Robbie wanted to do during a sleepover.

While Jones frames his memoir as a story of overcoming adversity through "persistence and tenacity," we must recognize that his temporary discomfort as a white child on the reservation exists in a different universe from the multigenerational trauma experienced by Indigenous peoples forced to navigate white-dominated spaces throughout their lives. Still, his reflection offers a settler's acknowledgment of privilege and perspective that too rarely enters mainstream discourse.

The Publishing Pipeline: Who Gets to Tell the Story?

This Morning Voice episode inadvertently highlights a persistent reality of American publishing: white memoirs about Indigenous spaces often find publishers more readily than Indigenous voices writing about their own communities.

Trinity Norris is creating a newspaper for her community because no such platform currently exists. Meanwhile, Jones has secured a publishing deal for his memoir about four childhood years on the Navajo Nation, and he has an upcoming book signing at Barnes & Noble.

The cruel mathematics of American publishing: four years of childhood observation by a white person outweighs centuries of Indigenous experience when it comes to determining whose stories deserve amplification. This isn't about Jones personally—it's about the structures that privilege certain narratives while marginalizing others.

This disparity isn't accidental—it's the product of a publishing industry that continues to view white experiences as universal and marketable, while treating Indigenous perspectives as niche or specialized. It's the same industry where "diversity initiatives" often mean publishing traumatic narratives of BIPOC suffering rather than stories of joy, complexity, and everyday life.

Trinity's work represents the necessary counternarrative—media created by and for Indigenous communities, centering Indigenous knowledge and experience without the mediating lens of outside interpretation. Her journalism doesn't just tell different stories; it transforms the very foundations of storytelling itself.

The Future is Indigenous

If there's hope to be found in this juxtaposition, it lies in the resilience and determination of Indigenous journalists like Trinity Norris, whose work ensures that Native stories will be told not through the colonial gaze but through authentic community voices.

The path forward requires more than individual storytellers—it demands structural transformation of media institutions and funding models. It requires white audiences to step back from expecting Indigenous stories to be translated or filtered for their comfort. It means supporting Indigenous-led media financially and recognizing their expertise without appropriation.

The revolution will not be mainstream-published. It will emerge from community newspapers, independent media platforms, and the persistent voices that refuse to be silenced.

For those of us committed to decolonial media, supporting initiatives like Trinity's capstone project represents a tangible step toward media justice. Subscribing to Indigenous-led publications, redirecting our attention and financial support away from corporate media toward community journalism, and acknowledging the expertise of Indigenous journalists covering environmental issues are all concrete actions we can take.

Keep This Analysis Coming: Support Three Sonorans

At Three Sonorans, we remain committed to highlighting stories and perspectives that mainstream media overlooks or misrepresents. Our analysis cuts through colonial frameworks to center the voices and experiences of communities fighting for justice across the borderlands.

Corporate sponsors or advertisers don't fund this work—it depends entirely on community support. By subscribing to our Substack, you ensure that this critical analysis continues to challenge dominant narratives and center the perspectives that matter most to our region's future.

What Indigenous-led media do you support? How have you seen mainstream coverage of environmental issues exclude Indigenous perspectives? What stories from your community need telling? Share your thoughts in the comments below, and let's continue building the media landscape our communities deserve.

The future of Arizona storytelling belongs to those who were here first—and their voices are rising.

Quotes

Trinity Norris: "A lot of times, I feel like in my opinion, a lot of stories that are being told are in a deficit lens for native folks. So I think for me, one of my goals is to strive to highlight our voices and show all the cool stuff that we're doing as native folks."

Trinity Norris on the Indigenous Resilience Center: "We know that tribal communities already have solutions for the environmental challenges they may face. And a lot of the time, financial needs are kind of like the setback."

Jay Jones on first witnessing the Intertribal Ceremony: "It was unbelievable to see when we drove there that particular day... there were Indigenous people coming from all over the place, walking, riding in wagons. A few had cars, but most were walking, riding horses, and they were in wagons. And it's like, is this 1967 or 1867?"

Jay Jones on watching Westerns with Navajo friends: "Here I am, you know, I'm here with these Native Americans, these Navajos, watching them get annihilated. And I had this terrible, terrible, uncomfortable feeling come over me. And Joe said, well, that's the way they always depict us."

Jay Jones: "Robbie didn't really care because they had become so used to seeing it. And it's very unfortunate, you know, that it took place because, you know, the way white people ostracize and demonize the Native American, not just the Navajo, but all over reservations throughout the country."

Trinity Norris on her capstone project: "On the nation, we actually don't have a running newspaper at all... we did have a newspaper but it has since been retired... And so I'm kind of working my way to building that out and hopefully regenerating or reviving a newspaper of the sort."

People Mentioned and Notable Quotes

Trinity Norris - Tohono O'odham journalist, graduate student at U of A studying global media, works at Indigenous Resilience Center and for Tucson Spotlight "I just feel really grateful that people even want me to tell their stories, right? They feel comfortable enough for me to share their stories. They trust me enough."

Jay Jones - Author of "A Billagáana Boy Among the Navajo," retired financial advisor who lived on Navajo Nation as a child in the 1960s "I faced a lot of adversity. I didn't have a lot of love and support from my parents. I certainly didn't get a whole lot of love from a lot of the kids that I went to school with. I was bullied quite frequently."

Dr. Karletta Chief - Leader of the Indigenous Resilience Center at University of Arizona (mentioned by Trinity)

Caitlyn Schmidt - Co-founder of Tucson Spotlight (mentioned as having recruited Trinity)

Robbie Hubbard - Jay Jones' Navajo childhood friend

Joe Hubbard - Robbie's brother who commented on Western movies: "That's the way they always depict us."

Laura Begay - Navajo neighbor of Jay Jones who worked with his mother at the Bureau of Indian Affairs

Nodin Begay - Laura's son who became friends with Jay

"Grandma Begay" - Nodin's grandmother who lived in a traditional hogan west of Chinle

Have a scoop or a story you want us to follow up on? Send us a message!