🔥 From Geronimo to Chi'chil Biłdagoteel: The Apache Wars Never Ended, Supreme Court Rules Sacred Oak Flat Can Be Destroyed

Why the Supreme Court's betrayal of Oak Flat represents the modern face of settler colonialism

😽 Keepin’ It Simple Summary for Younger Readers

👧🏾✊🏾👦🏾

⛰️🙏 Oak Flat is a sacred place in Arizona where Apache people have held important religious ceremonies for over a thousand years. The U.S. government made a deal to give this land to a foreign mining company that wants to dig a huge hole to get copper from underground. ⚖️🚫 Today, the Supreme Court decided not to protect this sacred place, even though it would be like letting someone destroy a church or mosque for money.

🏛️✊ The Apache people are fighting back through the courts and asking other countries to help them protect their religious freedom. 🌍🤝 This is part of a much longer conflict between Native American tribes and the U.S. government over land and rights that has been going on for hundreds of years. 🕰️🪶

🗝️ Takeaways

⚖️ The Supreme Court refused to hear Apache Stronghold's case, allowing Resolution Copper to destroy the Oak Flat sacred site

🏔️ Oak Flat (Chi'chil Biłdagoteel) is essential for Apache religious ceremonies that cannot be performed anywhere else

🏭 Foreign mining giants Rio Tinto and BHP plan to create a 1.8-mile-wide crater where the sacred site now stands

💰 The 2014 land swap was snuck into a defense bill without meaningful Apache consultation or public hearings

🌍 The Apache have petitioned the UN for help after U.S. courts consistently ruled against Indigenous religious freedom

💧 The mine will consume 250 billion gallons of groundwater in drought-stricken Arizona over its lifetime

⚔️ This continues the Apache Wars that began with Cochise and Geronimo—colonialism with different weapons

🤝 The resistance includes legal challenges, international diplomacy, and on-ground spiritual protection of the site

The Sacred Ground They Cannot Steal: How the Supreme Court's Oak Flat Decision Continues 150 Years of Apache Resistance

Chi'chil Biłdagoteel – Oak Flat.

For the Apache people, these words carry the weight of creation itself, the spiritual heartbeat of a nation that has survived genocide, forced removal, and generations of systematic oppression.

Today, May 27, 2025, the United States Supreme Court delivered what many are calling the final blow to Indigenous religious freedom, refusing to hear Apache Stronghold's desperate plea to protect their most sacred site from corporate destruction.

But this is no ordinary legal defeat.

This is the continuation of a war that began with Cochise and Geronimo, a war that never truly ended – it just changed weapons. Instead of cavalry and rifles, today's colonizers wield environmental impact statements and mining permits. Instead of bounties on Apache scalps, they offer jobs and economic development. The methods have evolved, but the goal remains the same: the complete subjugation of Indigenous peoples and the theft of their sacred relationship to the land.

The Supreme Court's Shameful Silence

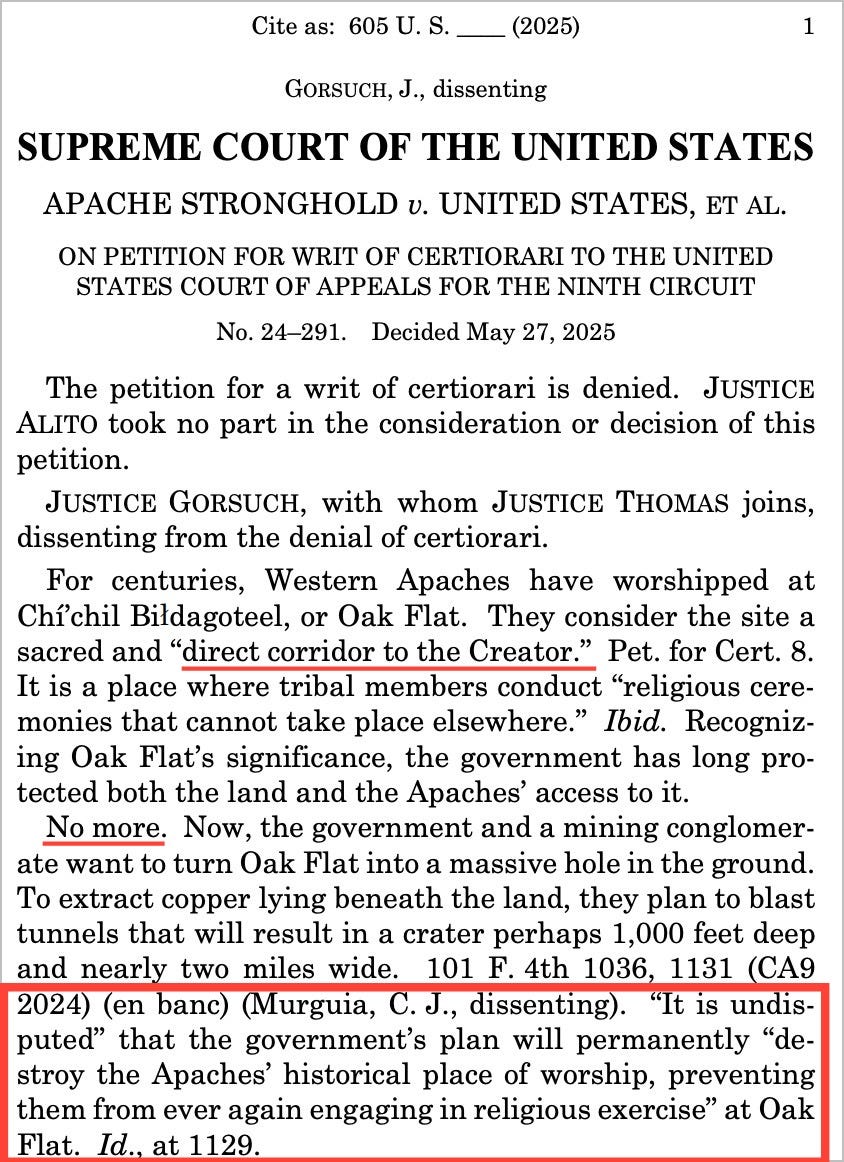

In a terse order that will echo through Indigenous communities for generations, seven justices of the Supreme Court refused to even consider whether the planned destruction of Oak Flat violates the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

Only Justices Neil Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas dissented, with Gorsuch writing that the Court's "decision to shuffle this case off our docket without a full airing is a grievous mistake -- one with consequences that threaten to reverberate for generations."

Justice Samuel Alito recused himself from the case, likely due to his financial stake in BHP, one of the mining giants behind Resolution Copper. The irony is bitter – a justice who has built his career on defending religious liberty couldn't be bothered to protect Indigenous sacred sites because it might hurt his stock portfolio.

The majority's silence speaks volumes.

They couldn't even be bothered to explain why Apache religious freedom matters less than Christian, Jewish, or Muslim sacred sites. As the San Carlos Apache Tribe pointed out in their petition to the United Nations:

"It is highly unlikely that this mining project would have been approved...were it proposed beneath a place of religious significance to a Christian denomination."

Chi'chil Biłdagoteel: More Than Sacred Ground

To understand what was lost today, you must understand what Oak Flat means to the Apache people. Known in Apache as Chi'chil Biłdagoteel, this 6.7-square-mile area in Arizona's Tonto National Forest isn't just another pretty camping spot – it's the spiritual equivalent of Mount Sinai, Vatican City, or Mecca.

For over a millennium, Apache women have gathered at Oak Flat for their Sunrise Ceremony, a sacred rite of passage that transforms girls into women and connects them to the White Painted Woman, the Apache deity of fertility and renewal. The oak trees that give the place its English name provide acorns that are ground into sacred meal. Springs bubble up from the earth with water considered holy, used in ceremonies that cannot be replicated anywhere else.

This is where the Ga'an – the mountain spirits who serve as messengers between the Apache people and Usen, the Creator – are said to dwell. These aren't quaint folk beliefs; they are the living theology of a people who have maintained their spiritual practices despite centuries of forced Christianization, boarding school trauma, and cultural genocide.

Naelyn Pike, a young Apache woman who had her Sunrise Ceremony at Oak Flat, testified before Congress at age 13 about what the site means to her people:

"On the fourth day, I became 'the white-painted woman.' My godfather and the Ga'ans painted my face with glesh, white clay from the ground, representing my entrance into a new life."

That white clay can only come from Oak Flat. Those ceremonies can only take place in that specific location. When Resolution Copper, a foreign corporation, turns Chi'chil Biłdagoteel into a crater 1.8 miles wide and over 1,000 feet deep, they won't just be destroying land – they'll be committing spiritual genocide.

The Corporate Colonizers: Resolution Copper's Assault

Resolution Copper is no ordinary mining company – it's a joint venture between two of the world's largest extractive corporations, Rio Tinto and BHP, with deep ties to foreign governments and a track record of destroying Indigenous sacred sites for profit.

Rio Tinto, the majority owner, gained international infamy in 2020 when it deliberately destroyed 46,000-year-old Indigenous rock shelters at Juukan Gorge in Western Australia – some of the oldest known sacred sites on Earth.

The company's executives later admitted they knew the cultural significance of what they were destroying but proceeded anyway because the iron ore underneath was simply too valuable to leave in the ground.

Rio Tinto's largest shareholder is Chinalco, owned and controlled by the Chinese government. So when we talk about protecting American sacred sites from foreign exploitation, we're literally talking about preventing Chinese state-owned entities from strip-mining Indigenous holy ground for copper that will primarily benefit overseas markets.

The proposed mine would extract an estimated 40 billion pounds of copper over its 60-year lifespan, generating approximately $1 billion annually for Arizona's economy. However, those numbers conceal the true cost: the permanent destruction of irreplaceable sacred sites, the depletion of already scarce desert groundwater, and the creation of 1.6 billion tons of toxic waste that will necessitate perpetual management.

The Sneaky Legal Maneuver: How Congress Sold Out the Apache

The path to today's Supreme Court betrayal began in December 2014, when Senators John McCain and Jeff Flake pulled off one of the most underhanded political maneuvers in recent memory. In the final hours before Congress passed the must-pass National Defense Authorization Act, they slipped in a rider – Section 3003 – that had nothing to do with national defense and everything to do with corporate welfare.

This provision, known as the Southeast Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Act, mandated that the U.S. Forest Service transfer 2,422 acres of Oak Flat to Resolution Copper in exchange for 5,376 acres of privately owned land elsewhere in Arizona. On paper, it sounds like a good deal – more land for the public, right?

But this wasn't just any land swap.

Oak Flat had been protected from mining since 1955, when President Dwight Eisenhower withdrew it from mineral entry specifically because of its cultural and environmental significance. For nearly 70 years, that protection remained in place. It took a backroom deal attached to a defense bill to undo seven decades of conservation.

The Apache people were never meaningfully consulted. No hearings were held on the merits of destroying one of their most sacred sites. Congressional leaders simply decided that corporate profits mattered more than Indigenous religious freedom, and they buried their betrayal in legislation that had to pass to fund the military.

Representative Raúl Grijalva, whose district includes Oak Flat, has spent years fighting to reverse this injustice through his Save Oak Flat Act. But despite overwhelming public support – polls show 74% of Americans oppose the mine – Congress has refused to act.

From Cochise to Chi'chil Biłdagoteel: The Unbroken Chain of Apache Resistance

To truly understand today's Supreme Court decision, you have to understand that the battle for Oak Flat is not separate from the Apache Wars of the 19th century – it's their direct continuation. The same colonial logic that drove General George Crook to hunt Geronimo through these same mountains now drives Resolution Copper to blast apart Apache sacred sites.

In the 1870s, the U.S. government's strategy was simple: break Apache resistance by destroying their connection to the land. They forced thousands of Apache people onto the San Carlos Reservation, which they themselves called "Hell's Forty Acres" because of its barren, unsuitable conditions. They kidnapped Apache children and sent them to boarding schools designed to "kill the Indian, save the man." They outlawed Apache religious practices and punished anyone caught performing traditional ceremonies.

But the Apache never stopped returning to Oak Flat.

Even during the height of the Apache Wars, when traveling off-reservation could mean death, families would slip away to perform the sacred ceremonies that could only happen in that place. When Geronimo finally surrendered in 1886, it wasn't because he had given up hope – it was because he believed the government's promise that his people would eventually be allowed to return to their ancestral lands.

That promise, like so many others, was broken. Geronimo and his followers were shipped off to Florida as prisoners of war, then to Alabama, and finally to Oklahoma, where many died far from the mountains they loved. But some Apache families remained, and they never forgot where their sacred places were.

During the 20th century, as legal restrictions on Indigenous religious practice gradually eased, Apache families began returning openly to Oak Flat for ceremonies. The site became a symbol of cultural survival – proof that no amount of oppression could sever the spiritual bonds between the Apache people and their ancestral lands.

Now, in the 21st century, that centuries-old resistance faces its greatest test. The weapons have changed, but the goal remains the same: to finally and permanently sever the Apache connection to Chi'chil Biłdagoteel.

Environmental Racism and Water Wars in the Sonoran Desert

The Oak Flat case isn't just about religious freedom – it's a textbook example of environmental racism, the systematic targeting of communities of color for toxic waste dumps, polluting industries, and resource extraction projects that would never be tolerated in wealthy white neighborhoods.

Resolution Copper's mine will consume an estimated 250 billion gallons of groundwater over its lifespan – enough water to supply the city of Tucson for over six years. In a state where every drop of water is precious and climate change is intensifying droughts, this represents a massive transfer of wealth from public resources to private profit.

The environmental impact will extend far beyond Oak Flat itself. The proposed "block caving" mining method will literally cause the surface to collapse, creating a subsidence zone that could affect groundwater flows across thousands of acres. The mine will also generate 1.6 billion tons of tailings – toxic waste that will require perpetual monitoring and maintenance to prevent contamination of soil and water.

This is the same pattern of environmental racism that has devastated Indigenous communities across the Southwest. On the Navajo Nation, over 500 abandoned uranium mines remain uncleared, more than 30 years after mining stopped, continuing to poison water sources and cause elevated rates of cancer and birth defects. The 1979 Church Rock uranium mill spill released more radioactive material into the environment than Three Mile Island, but because it happened on Navajo land, it received a fraction of the media attention.

The parallels to Oak Flat are chilling. A foreign-owned corporation promises jobs and economic development while the real costs – environmental degradation, public health impacts, and cultural destruction – are borne by Indigenous communities with little political power to resist.

The Legal Travesty: How Courts Failed Indigenous Rights

Apache Stronghold's legal challenge to the Oak Flat land swap has been winding its way through federal courts for over four years. At every level, judges have found new ways to deny Apache religious freedom while maintaining the fiction that they're applying the law fairly.

The case began in January 2021, when Apache Stronghold filed suit, arguing that transferring Oak Flat to Resolution Copper violates the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), which requires the government to demonstrate a compelling interest before substantially burdening a person's religious practice. The argument was straightforward: destroying the physical location where Apache ceremonies must take place constitutes the ultimate substantial burden on religious exercise.

But federal courts have twisted themselves into legal pretzels to avoid applying RFRA to Oak Flat. A three-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals initially ruled 2-1 that the land transfer doesn't substantially burden Apache religion because the government isn't forcing anyone to violate their beliefs – it's just making it impossible for them to practice their religion in the future.

This logic is both absurd and dangerous. By this reasoning, the government could demolish every church, mosque, and synagogue in America and claim it's not violating religious freedom as long as it doesn't explicitly prohibit worship. It could seize Vatican City for a shopping mall and argue that Catholics are free to practice their religion somewhere else.

When Apache Stronghold requested an en banc review by the full Ninth Circuit, eleven judges reheard the case. The March 2024 decision was even worse: a 6-5 ruling that doubled down on the panel's reasoning and added new insults to injury. The majority opinion suggested that Apache religious practices could simply be relocated elsewhere, demonstrating a fundamental misunderstanding of land-based Indigenous spirituality.

The five dissenting judges understood the stakes. They wrote that the majority had "tragically erred" and that the ruling "eviscerates the promise of religious freedom for Native Americans." They recognized that for Indigenous peoples, the land itself is sacred, not just a convenient location for worship, but an integral part of the spiritual practice.

The International Arena: Apache Diplomacy at the United Nations

Facing consistent defeats in U.S. courts, the San Carlos Apache Tribe has taken its case to the international arena, petitioning the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination to pressure the United States into respecting Apache human rights.

Their petition, filed in April 2024, lays out a devastating case that the Oak Flat land transfer constitutes racial discrimination under international law. The tribe argues that the U.S. government is applying a clear double standard: protecting sacred sites of mainstream religions while enabling the destruction of Indigenous holy places for corporate profit.

The petition states: "It is highly unlikely that this mining project would have been approved...were it proposed beneath a place of religious significance to a Christian denomination. The fact that the United States will allow the destruction of Chi'chil Biłdagoteel, but protect other religious sites, demonstrates a grotesque exemplar of racial discrimination against the Tribe and Indigenous peoples more generally."

This international strategy reflects the sophisticated diplomatic approach that Indigenous nations have increasingly adopted when domestic legal systems fail them. By framing Oak Flat as a human rights issue rather than just a domestic legal dispute, the Apache are forcing the international community to confront America's ongoing colonialism.

The UN petition also highlights how the Oak Flat case fits into broader patterns of discrimination against Indigenous peoples worldwide. From the Amazon rainforest to the Arctic tundra, extractive industries routinely destroy Indigenous sacred sites with the blessing of national governments that would never tolerate similar destruction of non-Indigenous religious places.

The Borderlands Context: Colonialism Never Ended in Southern Arizona

Living here in the borderlands of Southern Arizona, you see the continuities between past and present forms of colonialism every day. The same mountains where Cochise and Geronimo fought for Apache sovereignty now host Border Patrol checkpoints and surveillance towers. The same valleys where Spanish missionaries built churches on top of Indigenous sacred sites now feature detention centers and deportation courts.

Oak Flat sits at the heart of this colonial landscape, surrounded by the infrastructure of ongoing conquest. To the south, the militarized border wall cuts through traditional Indigenous territories, separating the Tohono O'odham Nation from relatives in Mexico and disrupting wildlife migration corridors that have existed for millennia. To the north, the sprawling suburbs of Phoenix consume ever more water and land, pushing deeper into the Sonoran Desert with each passing year.

The proposed Resolution Copper mine represents the next phase of this colonial expansion. Where 19th-century settlers sought gold and silver, 21st-century corporations seek the copper needed for electric vehicles and renewable energy infrastructure. The rhetoric has changed – now it's about fighting climate change and reducing dependence on foreign minerals – but the logic remains the same: Indigenous land and Indigenous rights are acceptable sacrifices for the supposed greater good.

This is particularly galling when you consider that much of the copper from Oak Flat will likely be exported to China for processing, then imported back to the United States as finished products. We're destroying Apache sacred sites to feed Chinese manufacturing, then pretending it's about American energy independence.

The parallels to historical patterns of colonial extraction are exact. Spanish colonizers shipped silver from Potosí to Europe, devastating Indigenous communities for the benefit of distant empires. British colonizers extracted rubber and tin from Southeast Asia, leaving environmental degradation and social disruption in their wake. American corporations are simply continuing this tradition, using Oak Flat copper to power the global economy while Apache people bear the costs.

Resistance in the Trump Era: Standing Rock to Oak Flat

The battle for Oak Flat cannot be separated from the broader Indigenous resistance movement that has defined the Trump era and will continue beyond it. From Standing Rock to Line 3, from Bears Ears to Oak Flat, Indigenous communities have been forced to fight for their very survival against an extractive capitalism that recognizes no limits and respects no sacred boundaries.

The Standing Rock water protectors showed the world what modern Indigenous resistance looks like: prayer camps and direct action, traditional ceremony and social media campaigns, tribal sovereignty and international solidarity. The movement's slogan – "Water is Life" – captured something essential about Indigenous worldviews that non-Indigenous people are only beginning to understand.

Oak Flat represents both the continuation of that resistance and its next evolution. Where Standing Rock was about stopping a pipeline, Oak Flat is about preventing the permanent destruction of a sacred site. Where Standing Rock brought together hundreds of tribes, Oak Flat has garnered support from 21 federally recognized tribes in Arizona, as well as faith leaders from multiple religious traditions.

The tactics have evolved, too. Apache Stronghold has combined traditional legal challenges with international human rights advocacy, grassroots organizing, and high-profile media campaigns to achieve its goals. They've held prayer vigils at the White House and testimony sessions before Congress. They've built alliances with environmental groups, rock climbers, and advocates for religious freedom.

Most importantly, they've never stopped asserting their fundamental right to exist as Apache people in relationship to Apache land. Wendsler Nosie Sr., the founder of Apache Stronghold, has literally moved to Oak Flat, establishing a permanent camp to physically protect the sacred site. His presence there is both a spiritual practice and a political statement:

"This is Apache land, and we're not going anywhere."

The Ripple Effects: What Oak Flat Means for Indigenous Rights

Today's Supreme Court decision will have far-reaching consequences that extend far beyond Oak Flat itself. By refusing to protect one of America's most significant Indigenous sacred sites, the Court has essentially declared open season on Native religious freedom.

If the destruction of Chi'chil Biłdagoteel doesn't violate the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, then no Indigenous sacred site is safe. Mining companies and other extractive industries will point to this precedent whenever Indigenous communities try to protect their holy places. "Even Oak Flat wasn't protected," they'll argue, "so why should your site be any different?"

The decision also signals the Court's broader retreat from protecting minority rights. This is the same Court that has gutted voting rights protections, weakened civil rights enforcement, and consistently favored corporate interests over individual rights. The Apache are just the latest community to discover that constitutional protections only extend so far when real money is at stake.

For Indigenous communities specifically, the Oak Flat decision confirms what many have long suspected: that despite all the official rhetoric about government-to-government relationships and tribal sovereignty, Indigenous rights remain subordinate to corporate profits when push comes to shove.

The environmental implications are equally troubling. If sacred Indigenous sites can be destroyed for copper mining, what's to stop similar destruction for lithium extraction, oil drilling, or any other extractive activity that corporations deem profitable? The logic that prioritizes short-term economic gains over long-term environmental and cultural preservation threatens far more than Oak Flat alone.

Water, Copper, and Climate Colonialism

The bitter irony of the Oak Flat mine is that much of the copper will supposedly be used for "green" technology – electric vehicle batteries, solar panels, and wind turbines that are essential for fighting climate change. Corporate PR departments love to frame resource extraction as environmental heroism: "We're saving the planet by destroying this mountain!"

But this narrative obscures the fundamental injustice of what scholars call "climate colonialism" – the way that environmental solutions often reproduce the same patterns of exploitation that created environmental problems in the first place. Indigenous communities, who contribute least to climate change, are forced to sacrifice their sacred sites and natural resources for technological fixes that primarily benefit wealthy consumers in distant cities.

The same dynamic plays out across the Southwest, where solar farms sprawl across Indigenous territories and lithium mines threaten sacred sites in Nevada and California. The renewable energy transition, for all its necessity, is being built on the same colonial foundations that powered fossil fuel extraction: Indigenous land is taken, Indigenous rights are ignored, and Indigenous communities bear the environmental and cultural costs.

Meanwhile, the mine's water consumption – 250 billion gallons over its lifetime – represents a massive subsidy to corporate profits at public expense. That groundwater belongs to all Arizonans, not just to Resolution Copper shareholders. In a state facing severe drought and growing water shortages, every gallon pumped for mining is a gallon not available for municipal use, agriculture, or ecosystem preservation.

The company's promises about water recycling and technological innovation ring hollow when considering their track record. Rio Tinto's mines around the world have left behind contaminated watersheds, depleted aquifers, and toxic legacies that communities deal with for generations. There's no reason to believe Oak Flat will be any different.

Building Solidarity: Lessons from La Resistencia

As a Chicano living in the borderlands, I see clear parallels between the Apache struggle for Oak Flat and broader social justice movements throughout the Southwest. The same forces that seek to destroy Indigenous sacred sites also militarize our borders, criminalize our communities, and exploit our labor.

The resistance movements fighting these injustices share common ground in their commitment to protecting la tierra – the land that sustains us physically, culturally, and spiritually. Whether it's Apache people protecting Chi'chil Biłdagoteel, Chicano families fighting gentrification in Barrio Viejo, or immigrant communities organizing against deportation raids, the struggle is fundamentally about the right to exist in relationship to place.

This is why solidarity between Indigenous communities and other communities of color is so essential. We face the same systems of oppression, even if they manifest in different ways. The colonialism that seeks to destroy Oak Flat is the same colonialism that seeks to wall off the border, the same capitalism that prioritizes profit over people, the same white supremacy that treats communities of color as expendable.

Building that solidarity requires more than just showing up for each other's protests, though that matters too. It requires developing a shared understanding of how systems of oppression intersect and a shared vision of what liberation might entail. It requires recognizing that Indigenous sovereignty isn't just an Indigenous issue – it's a model for how all communities can relate to land and one another in more just and sustainable ways.

The Path Forward: La Lucha Continúa

Despite today's Supreme Court setback, the fight for Oak Flat is far from over. Apache Stronghold has vowed to continue its legal challenges, and several other lawsuits are still pending in federal courts. The San Carlos Apache Tribe has filed a separate suit arguing that the 1852 Treaty of Santa Fe gives them ongoing rights to Oak Flat that supersede the 2014 land swap legislation.

Environmental groups have their own lawsuit challenging the adequacy of the environmental review process, arguing that the Forest Service failed to adequately analyze the mine's impacts on water, wildlife, and surrounding communities. If successful, this challenge could compel the government to conduct a more thorough environmental impact statement, which might reveal costs that the mining industry would prefer to keep hidden.

Congressional action remains possible, though unlikely in the current political climate. Representative Grijalva's Save Oak Flat Act would repeal the 2014 land swap legislation and permanently protect the site from mining. The bill has broad support among Democrats and some Republicans, but it needs sustained public pressure to overcome the lobbying efforts of the mining industry.

International pressure is also building. The UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination is expected to issue findings on the Apache petition sometime in 2025, potentially creating diplomatic pressure on the Trump administration to halt the land transfer. However, given Trump's openly hostile stance toward Indigenous rights and his administration's stated commitment to fast-tracking the Oak Flat project, UN pressure is unlikely to sway his administration.

While UN resolutions aren't legally binding, they could strengthen future legal challenges and increase international scrutiny of America's treatment of Indigenous peoples. The irony is bitter: the Apache may have to rely on international human rights bodies to protect their religious freedom from their own government.

Most importantly, the resistance on the ground continues. Apache families continue to hold ceremonies at Oak Flat, asserting their spiritual connection to the land through practice rather than just legal argument. The prayer camp established by Wendsler Nosie Sr. serves as a constant reminder that this isn't just a legal or political battle – it's a spiritual one.

Supporting the Struggle: How to Get Involved

The Oak Flat battle requires sustained support from individuals who recognize that Indigenous rights are human rights and that environmental justice is inextricably linked to social justice. Here are concrete ways to get involved:

Financial Support: Apache Stronghold relies on donations to fund their legal challenges and grassroots organizing. Even small contributions help cover travel costs for court hearings, legal filing fees, and community organizing expenses.

Political Pressure: Contact your representatives in Congress and demand they support the Save Oak Flat Act. If you live in Arizona, put particular pressure on Senators Mark Kelly and Kyrsten Sinema, who have remained shamefully silent on this issue despite representing the state where Oak Flat is located.

Educational Work: Share information about Oak Flat on social media, write letters to newspaper editors, and talk to friends and family about why this issue matters. Many people still don't know about the threat to Oak Flat or understand the broader implications for Indigenous rights.

Solidarity Actions: Attend rallies and prayer vigils when they happen in your area. Join or support local Indigenous rights organizations. Make connections between the Oak Flat struggle and other social justice issues in your community.

Economic Pressure: Research the corporate connections of Rio Tinto and BHP. Pressure pension funds, university endowments, and other institutional investors to divest from companies involved in destroying Indigenous sacred sites.

Media Accountability: Challenge mainstream media outlets when they frame the Oak Flat conflict as a simple jobs-versus-environment story. Push them to center Indigenous voices and address the religious freedom and human rights dimensions of the case.

A Note of Hope: La Esperanza Nunca Muere

Today's Supreme Court decision is devastating, but it's not the end of the story. The Apache people have survived 500 years of colonialism, and they're not going to give up now. Their resistance has deep roots in traditional knowledge and spiritual practice that no court can destroy.

More broadly, the Oak Flat struggle has awakened a new generation of Indigenous activists and their allies to the ongoing realities of colonialism in America. Young Apache people, such as Naelyn Pike, are speaking truth to power in ways that inspire people across Indian Country and beyond. The movement has built powerful coalitions that will outlast any single legal battle.

The fight for Oak Flat is also part of a broader global movement for Indigenous rights that is gaining momentum despite ongoing setbacks. From the Amazon to the Arctic, Indigenous communities are asserting their sovereignty and demanding that the world recognize their relationship to land as legitimate and valuable. This movement won't be stopped by one Supreme Court decision, no matter how devastating.

Most importantly, the Apache people have something that Resolution Copper will never have: a genuine, spiritual connection to the land that transcends any legal document or corporate profit statement. Chi'chil Biłdagoteel will always be Apache land, no matter what the courts say or what the mining companies do. That truth is written in the landscape itself, in the ceremonies that have been held there for over a thousand years, in the prayers that rise from that place like smoke from sacred fires.

La lucha continúa – the struggle continues. And as long as there are Apache people who remember the songs of their ancestors and the stories of their land, there will be resistance to those who would destroy what is sacred for what is profitable.

To stay informed about the ongoing struggle for Oak Flat and other Indigenous rights issues throughout the borderlands, please consider supporting Three Sonorans by subscribing to our Substack. Your support helps us continue providing independent coverage of the stories that mainstream media too often ignores.

What questions do you have about the Oak Flat case and its broader implications for Indigenous rights in the borderlands?

How do you see the connections between this struggle and other social justice movements in your own community?

Have a scoop or a story you want us to follow up on? Send us a message!

First, I have swallowed my bile and hit the "heart" symbol. I do NOT love or like the news you have shared, and I devoutly wish substack would give us other options (e.g., sad, angry).

More to the point, I am appalled by the savage racism that not only still exists but has, if anything, blossomed and increased substantially in the last fifteen years. One can only imagine what sorts of distortions history textbooks will present to future generations.

Finally, you reported Alito recused himself, while Gorsuch and Thomas dissented. Forgive for asking, but what were Kagan, Jackson, and Sotomayor smoking, and how do THEY -- the so-called "liberals" of the Extreme Court -- justify their votes? This case SHOULD have been heard.

I am reminded of the old adage that cynical lawyers endlessly repeat. "If the facts are on your side, argue facts. If the law is on your side, argue legalities. If neither is on your side, depend on technicalities." I am afraid the government will draw support from some hideous "technicalities," and I cannot express my outrage over the continued mistreatment of the Apache and other Indigenous Peoples.

Thank you for reporting on this travesty of Indigenous justice. 😠I’m heartbroken by it; been following it since the beginning. My personal connection with Oak Flat began in 1995 as a rock climber living in Tucson, and continued/expanded as I became aware of deeper issues and fell in love with Land itself. I had experiences in Oak Flat that western logical rationalism could not explain: intense spirit interactions and connection with disembodied energies. I feel deeply for the Apache people and their continuing relationship with the land and spirits there. Colonialism marches on nonstop with its goal of possessing the earth in its entirety. 😔