🌵 Bulldozed Dreams: The Systematic Erasure of Tucson's Mexican-American Heart

From La Calle to luxury condos: tracking 60 years of displacement in the Old Pueblo

😽 Keepin’ It Simple Summary for Younger Readers

👧🏾✊🏾👦🏾

🌆📢 Imagine if someone came to your neighborhood and said, "We need to tear down all your friends' houses, your school, the corner store where you buy candy, and the park where you play - because we want to build a big concrete building for business meetings." That's basically what happened to a neighborhood called Barrio Viejo in Tucson in the 1960s.

🏡🎎 This neighborhood was really special because families from Mexico, China, and other places all lived together and created this amazing community where kids could walk to everything they needed and grandparents lived close to their families. But city leaders thought tourists wouldn't want to visit Tucson if they saw this authentic Mexican-American neighborhood, so they destroyed it and built the Convention Center instead.

🏢🏠 Now the same thing is happening again, but more slowly. Rich people are buying houses in neighborhoods where families have lived for generations, fixing them up, and selling them for so much money that the original families can't afford to live there anymore. It's like if your neighbor sold their house and suddenly all the houses on your street cost a million dollars - your family might have to move far away even though you'd done nothing wrong.

🤝💪 The good news is that people are fighting back by organizing, sharing their stories, and creating new ways to keep housing affordable so families can stay in their communities.

🗝️ Takeaways

🏠 80 acres of irreplaceable multicultural community were bulldozed in the 1960s to build the Tucson Convention Center

📈 Housing prices in historically Latino neighborhoods are skyrocketing, with the first $1.5M home sold in Barrio Viejo and Diane Keaton's house reselling for $2.6M

🏗️ City tax incentive programs (GPLET) are contributing to gentrification by subsidizing market-rate development without requiring affordable housing

👥 The original Barrio Viejo was uniquely multicultural, with Chinese-Americans, African-Americans, and Mexican-Americans creating an integrated community that city leaders saw as "undesirable"

💸 Current median rent increases of 30% are forcing families who've lived in these neighborhoods for generations to move away from elderly parents and community networks

🎭 Community resistance is growing through projects like Barrio Stories, neighborhood coalitions, and community land trusts that keep housing permanently affordable

📊 The displacement isn't accidental - it's driven by specific policy choices that prioritize developer profits over community stability

🌱 Historic neighborhoods like Barrio Viejo were models of sustainable development with adobe cooling, walkability, and local food systems that modern developments can't match

The Ghost of Barrio Viejo: When Progress Displaces People

¡Órale, mi gente! Today, we're diving deep into a story that cuts to the very heart of Tucson—literally. It's a story about a neighborhood that was murdered by "progress," and how that same violence is happening again, just more slowly this time.

Standing in the shadow of the Tucson Convention Center today, you might see clean concrete plazas, manicured landscaping, and the occasional tourist snapping photos. What you won't see are the ghosts - the abuelitas hanging laundry on lines stretching between ancient adobe walls, kids playing fútbol in dusty callejones, families gathering in the evenings to share stories and caldo. You won't hear the mariachi music drifting from La Plaza Theatre or smell the fresh tortillas from the corner market where your credit was as good as your word.

This is the story of Barrio Viejo—once the beating heart of Tucson, now a cautionary tale about what happens when politicians and developers decide that culture and community are obstacles to profit.

La Calle: The Street That Was Our World

To understand what we lost, we need to understand what Barrio Viejo was.

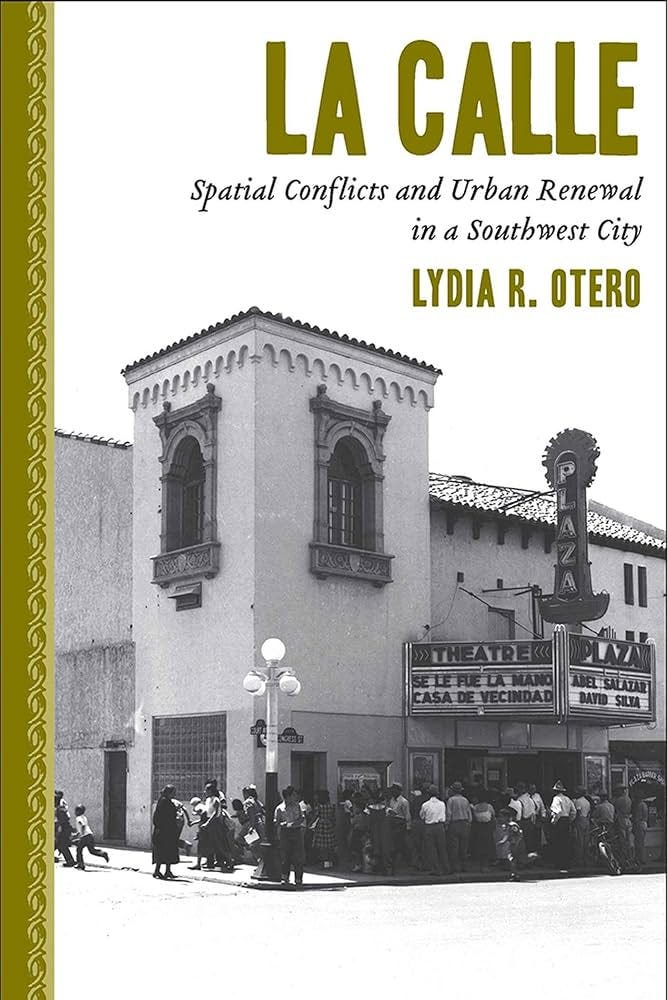

Historian and author Lydia Otero, whose own family lived in the neighborhood for generations, describes it best in her groundbreaking book La Calle: Spatial Conflicts and Urban Renewal in a Southwest City.

As she explains in a recent oral history video (above) about the area:

"My parents were both born in this barrio here, sometimes referred to as Barrio Viejo. Most Tucsonenses who have lived in Tucson for more than 50 years have a connection to La Calle in this place."

Barrio Viejo wasn't just Mexican-American—it was beautifully, authentically multicultural in ways that today's diversity initiatives can only dream of achieving.

“That area, too, I must say, was the most multi-ethnic community ever in Tucson, ever," Otero recalls. "I knew a lot of Chinese-Americans who spoke Spanish. I met African-Americans who spoke Spanish. That mixture was very, very unique."

According to Otero's research, the 1930s WPA Guide described the area:

"Residents of Mexican extraction comprise around 45 percent of the Old Pueblo population. Most of them live in Old Town, called El Barrio Libre... This is the exclusive Mexican shopping district... In most of the bars around Meyer [Avenue], Negro chefs are busy concocting hot chili sauce to pour over barbequed short ribs."

This was a place where cultures didn't just coexist—they blended, creating something uniquely Tucsonan. Families like Otero's had roots stretching back centuries. Her paternal grandmother, Alta Gracia Otero, lived there in the early 1900s, making a living selling bootleg alcohol during Prohibition.

These weren't newcomers or transients - these were the people who made Tucson.

The Murder of a Neighborhood

But by the 1960s, city leaders had decided that this authentic, vibrant community was a problem. Why? Because they wanted to rebrand Tucson as an all-American tourist destination, having a thriving Mexican-American neighborhood at the heart of downtown didn't fit their vision.

According to the University of Arizona News, Otero's research uncovered a deliberate campaign: "It seemed Tucson decision-makers had historically made blatant efforts to phase out established communities south of downtown to advance local tourism." The goal was to transform Tucson's image from a Mexican border town to a sanitized Old West fantasy that would appeal to Anglo tourists.

On March 1, 1966, Tucson voters approved urban renewal plans that would prove devastating. The result? As detailed by Zocalo Magazine, "the city razed 80 acres of irreplaceable culture, shops, homes, restaurants, entertainment venues (notably La Plaza Theatre) – wiping out over 100 years of historically significant buildings and scattering its residents asunder."

Let me repeat that: 80 acres of irreplaceable culture. Gone. Bulldozed. Erased.

The human cost was immeasurable. Families that had lived in the same neighborhood for generations were scattered to the wind. Business owners who had served the community for decades lost everything.

Children who had grown up speaking Spanish on the playground were suddenly told their culture wasn't welcome in the new Tucson.

The Second Coming: Gentrification 2.0

Here's where the story gets personal and urgent in the present tense. The same forces that destroyed Barrio Viejo in the 1960s are at work again, just more subtly this time. Instead of bulldozers, we have market forces. Instead of urban renewal, we have "revitalization." Instead of outright demolition, we have displacement through pricing.

The housing data tells a stark story. According to recent market analysis, Tucson's median home price hovers around $400,000. But these city-wide numbers hide the real crisis happening in historically Latino neighborhoods. As reported by the Arizona Daily Star, "The first $1.5 million home sold in Barrio Viejo, far outpacing anything else in the neighborhood."

Remember when actress Diane Keaton bought an adobe house in Barrio Viejo for $1.5 million in 2018 and sold it for $2.2 million in 2021? That's not just celebrity real estate—it's a symbol of how outside money is pricing out families who have called these neighborhoods home for generations.

Raul Ramirez, vice president of the Menlo Park Neighborhood Association, puts it bluntly in a recent Cronkite News report:

"Investors come in and are looking for these older neighborhoods … and the danger is it's displacing people. Because right now, everyone, regardless of gentrification, everybody is in a financial bind – that they need to sell their home. Although they can get a good chunk of money, what house can they go buy? Where?"

The Human Cost of "Progress"

Rebecca Renteria's story, reported in the Arizona Daily Star, illustrates the ongoing displacement:

"For Rebecca Renteria, who grew up on the west side and whose many family members are rooted in Menlo Park and Kroger Lane, gentrification means she can't afford to move closer to her widower father who lives near West Grant and North Silverbell roads. 'We've always been here. We can't talk about it in generations because we've always been here,'" said Renteria, a recent master's graduate in anthropology from the University of Arizona.

This is the cruelest irony: educated, accomplished community members like Renteria—people who embody the very success story our society claims to celebrate—are being priced out of their own neighborhoods. Their families helped build these communities, but now they can no longer afford to live in them.

Social workers note that gentrification has hidden effects. As one expert quoted in Cronkite News explained, gentrification creates "hidden effects and stresses on families" that extend beyond simple displacement. It fractures social networks, disrupts intergenerational care systems, and erodes the cultural fabric that makes communities resilient.

The Policy Machine Behind the Displacement

This isn't happening by accident. Like the urban renewal of the 1960s, today's gentrification is driven by specific policy choices made by elected officials who prioritize development profits over community stability.

Take the Government Property Lease Excise Tax (GPLET) program, which grants the city the authority to offer incentives for development in specific areas. According to Planetizen News, "Since its inception, Tucson has entered into 24 GPLET agreements, some of which converted affordable senior housing to luxury rentals."

A 2021 study by University of Arizona professor Gary Pivo found that while GPLET projects weren't the primary cause of gentrification, the program "could do more to help people and businesses being displaced" and should "look for opportunities to create affordable housing for people who earn less than $35,000 a year."

But here's the kicker: as neighborhood advocate Raul Ramirez points out, "Given all those incentives, you would think that they would be in a prime position to subsidize some low-income housing, but they don't, it's all market rate."

Fighting Back: Community Resistance Then and Now

The destruction of Barrio Viejo didn't happen without resistance. Otero's research uncovered the La Placita Committee, which fought to preserve the neighborhood. But as documented, "Despite the efforts of the La Placita Committee, the city razed 80 acres of irreplaceable culture."

Today's resistance is more organized and proactive. The Barrio-Neighborhood Coalition of Tucson is working to prevent the complete gentrification of remaining Latino neighborhoods. As reported by the Arizona Daily Star, there's "anger about escalating housing prices in the barrios and neighborhoods around downtown, the growing fears of displacement of longtime residents."

The STEM Analysis: Why This Matters Beyond Culture

As someone who approaches these issues with a STEM background, let me break down why this matters from a data and systems perspective:

Economic Efficiency: Destroying established communities and displacing long-term residents is economically wasteful. These families represent decades of investment in local networks, businesses, and institutions. Displacement fragments these networks and reduces overall community productivity.

Environmental Impact: Historic neighborhoods like Barrio Viejo were built with passive cooling, walkability, and resource efficiency that modern developments struggle to match. Adobe construction, narrow streets, and dense urban fabric create naturally sustainable communities. Replacing them with suburban-style development increases energy consumption and car dependency.

Public Health: Strong community networks provide health benefits that can't be replicated by medical interventions alone. When gentrification breaks up these networks, it creates measurable negative health outcomes, particularly for elderly residents and children.

Innovation Potential: The multicultural creativity that characterized Barrio Viejo represents exactly the kind of cross-cultural innovation that drives economic growth in the 21st century. Homogeneous communities are less innovative and adaptive than diverse ones.

The Diane Keaton Effect: When Celebrity Becomes Symbol

Let's talk about the elephant in the room - or rather, the movie star in the barrio. When Diane Keaton bought and renovated a house in Barrio Viejo, many people celebrated it as a preservation effort. And yes, she did preserve a historic building that might otherwise have crumbled.

But as Otero notes in the oral history video:

"The house that now we know is the Diane Keaton house, and you can see it was a series of smaller units that were combined into a big house. I remember it when it was a lot of Adobe units, and they didn't have roofs on them. They were pretty worn down."

The problem isn't preservation - it's who gets to stay and who gets priced out. When that house sold for $2.2 million (after being listed for $2.6 million), it sent a market signal that fundamentally changed the neighborhood's economics. As one community member noted in the video, "I read something in a magazine, or saw something on TV, that was talking about this neighborhood, and talking about Tucson… you know, when publicity like that gets out it ruins towns."

This represents what we might call the "celebrity gentrification effect" - when the presence of famous people in a neighborhood creates a media buzz that attracts outside investment and drives up prices faster than local incomes can keep pace.

What We Lost vs. What We Got

Let's do a clear-eyed comparison of what Barrio Viejo was versus what replaced it:

What We Lost:

80 acres of a walkable, mixed-use neighborhood

Affordable housing integrated with small businesses

A multicultural community where different ethnicities lived and worked together

Historic architecture adapted to the desert climate

Intergenerational families living in proximity

Local economy based on community relationships

Cultural venues like La Plaza Theatre

Authentic Mexican-American culture at the city's heart

What We Got:

A convention center that hosts corporate events

Parking lots and government buildings

Suburban-style development patterns

Car-dependent infrastructure

Separation of residential and commercial uses

A generic architecture that could be anywhere in America

The question we should be asking: Which version better served the actual residents of Tucson? Which was more economically sustainable? Which created more genuine community wealth?

The Resistance Continues: Current Community Organizing

Today's anti-gentrification organizing is learning from the failures of the 1960s. Instead of waiting for the bulldozers, communities are organizing proactively.

The Barrio-Neighborhood Coalition has been holding community forums to educate residents about their rights and organize collective responses. As reported by local media, these meetings have drawn over 100 people from various west-side, downtown, and university-area neighborhoods, indicating that the concern extends across multiple communities.

Key strategies include:

Community Land Trusts: The Pima County Community Land Trust has provided homes to 111 low- to moderate-income families since 2010 by purchasing land and keeping it permanently affordable. As executive director, Maggie Amado-Tellez explains that this model helps families build equity while preventing displacement driven by speculation.

Policy Advocacy: Community groups are advocating for inclusionary zoning requirements that would mandate the inclusion of affordable units in new developments, stronger tenant protections, and community benefit agreements for large projects.

Cultural Preservation: Projects like Barrio Stories help maintain community memory and cultural identity even as physical spaces change.

Economic Development: Supporting local businesses and entrepreneur development to ensure that community members can benefit from neighborhood improvements rather than being displaced by them.

The Numbers Game: What Real Anti-Displacement Policy Looks Like

If we're serious about preventing another Barrio Viejo-style erasure, we need policies backed by data and adequate funding. Here's what a real anti-displacement policy would look like:

Affordable Housing Requirements:

Mandate 20-30% affordable units in new developments over 20 units

Require affordability to be maintained for 99 years, not the current 15-30 year periods

Target affordability for families earning less than $35,000/year, not just "workforce housing"

Anti-Speculation Measures:

Implement transfer taxes on rapid property flips

Provide right-of-first-refusal for existing tenants when rental properties are sold

Create community land trusts to remove land from speculation permanently

Community Benefit Agreements:

Require developers receiving tax incentives to hire locally and provide community benefits

Mandate community input in all GPLET agreements

Create enforceable requirements for affordable housing in subsidized developments

Tenant Protections:

Despite state preemption, find creative ways to limit rapid rent increases

Provide legal assistance for tenants facing displacement

Create relocation assistance funds for families forced to move

Learning from Other Cities: What Works and What Doesn't

Tucson isn't unique in facing these challenges. Cities across the Southwest are grappling with similar displacement pressures. Let's examine what's worked elsewhere:

Austin, Texas: Created a displacement prevention fund that provides emergency assistance to families facing eviction or sudden rent increases. While not perfect, it's helped hundreds of families stay in their neighborhoods during transitions.

San Antonio, Texas: Implemented an anti-displacement policy that requires developers receiving city incentives to contribute to affordable housing funds. This creates a direct link between development profits and community benefits.

Portland, Oregon: Used inclusionary zoning and community land trusts to maintain affordable housing in gentrifying neighborhoods. While Portland still faces challenges, these policies have preserved thousands of affordable units.

What Doesn't Work:

Relying on market forces to provide affordable housing

Offering short-term affordability requirements that expire after 15-30 years

Treating gentrification as inevitable rather than as a policy choice

The Environmental Justice Angle

There is another crucial dimension to this story that's often overlooked: environmental justice. Barrio Viejo and similar neighborhoods aren't just culturally significant—they're models of sustainable urban development that we desperately need as climate change intensifies.

Historic adobe buildings offer natural cooling, which reduces energy consumption. Dense, walkable neighborhoods reduce car dependency and associated air pollution. Integrated mixed-use development reduces transportation emissions. Local food systems reduce the carbon footprint of daily life.

When we destroy these neighborhoods and replace them with suburban sprawl, we're not just committing cultural violence - we're making climate change worse. The families displaced from Barrio Viejo often ended up in car-dependent subdivisions on Tucson's periphery, increasing their carbon footprint and reducing their quality of life.

This is environmental racism in action: forcing low-income communities of color to live in less sustainable, more polluted areas while preserving or creating green, sustainable spaces for wealthy residents.

The Path Forward: Policy Recommendations

Based on the research and community organizing happening in Tucson, here are specific policy recommendations that could prevent future displacement:

Immediate Actions:

Moratorium on new GPLET agreements until community benefit requirements are strengthened

Creation of a displacement prevention fund with a dedicated revenue source

Expansion of community land trust programs

Mandatory community input requirements for all major development projects

Medium-term Policy Changes:

Inclusionary zoning ordinance requiring 25% affordable units in new developments

Commercial anti-displacement strategies to prevent loss of local businesses

Cultural preservation requirements for developments in historic neighborhoods

Transportation investments that connect affordable neighborhoods to job centers

Long-term Vision:

Community ownership models that keep land and buildings in community control

Cooperative economy development to build community wealth

Integration of affordable housing with climate resilience planning

Reparative investments in communities harmed by past urban renewal

What You Can Do: Getting Involved

This isn't just a story about the past - it's about choices we're making right now that will determine Tucson's future. Here's how you can get involved:

Learn and Educate:

Read Lydia Otero's book "La Calle" to understand the full history

Attend Barrio-Neighborhood Coalition meetings and community forums

Follow local housing policy discussions at City Council meetings

Share these stories with friends and family

Organize and Advocate:

Join neighborhood associations in affected areas

Support candidates who prioritize affordable housing and anti-displacement policies

Advocate for stronger community benefit requirements in development projects

Push for dedicated funding for affordable housing preservation

Support Community-Controlled Development:

Donate to organizations like Pima County Community Land Trust

Shop at local businesses in historically Latino neighborhoods

Support community development financial institutions that serve these areas

Volunteer with organizations doing tenant rights work

Stay Informed and Connected:

Subscribe to Three Sonorans Substack to stay informed about these issues

Follow local investigative reporting on housing and development

Attend public meetings where these decisions are made

Connect your neighbors to resources and organizing opportunities

A Note of Hope: Communities Fighting Back

Despite all the challenges, there are reasons to be hopeful. Communities across Tucson are organizing, learning from past mistakes, and building power to shape their own futures.

The fact that the Barrio Stories Project attracted 5,000 people demonstrates a hunger for authentic community stories and connection. The growth of the Barrio-Neighborhood Coalition demonstrates that people are willing to organize for change. The success of community land trusts demonstrates that alternative development models can be effective.

Most importantly, communities like Barrio Anita, Menlo Park, and others remain here, vibrant, and continue to fight. They're not waiting for permission or for perfect conditions - they're building the solutions they need.

As Lydia Otero notes in reflecting on her family's connection to these neighborhoods, "We own a piece of its history, and I'm glad that it's preserved the way it is, but it's not the feel, and it's not the people that I remember who once lived here, and it's not the energy that it doesn't have the energy that it once had."

The goal isn't to freeze neighborhoods in time - it's to ensure that the people who built and sustained these communities get to participate in and benefit from their evolution, rather than being displaced by it.

Supporting Community Media

Stories like this don't tell themselves. They require independent, community-rooted journalism that's willing to dig deep into complex issues and center community voices rather than developer PR and politician talking points.

That's why supporting Three Sonorans Substack matters. We're committed to covering these issues with the depth and community accountability they deserve. We're here in the borderlands, experiencing these changes firsthand, talking to the families affected, and following the money and policy decisions that shape our communities.

Your subscription helps us continue this work and ensures that community voices stay central to these conversations. In a media landscape dominated by corporate interests, independent community media is more crucial than ever.

¡Órale, we've covered a lot of ground today, from the systematic destruction of Barrio Viejo in the 1960s to the ongoing gentrification threatening Latino neighborhoods throughout Tucson. This story isn't just history - it's a blueprint for understanding how power operates in our city and what it takes to build community power strong enough to resist.

The ghost of Barrio Viejo haunts every planning meeting, every development proposal, every conversation about Tucson's future. The question is whether we'll learn from that history or repeat it.

What do you think? How do we ensure that Tucson's growth includes rather than displaces the communities that make our city unique? And what would it look like to build new development that strengthens rather than fragments our cultural fabric?

Have a scoop or a story you want us to follow up on? Send us a message!