🧬 Ancient DNA Reveals: Are We All Part Neanderthal?

Groundbreaking research shows how prehistoric interbreeding shaped modern humans

😽 Keepin’ It Simple Summary for Younger Readers

👧🏾✊🏾👦🏾

🦴 Scientists found the skeleton of a child in Portugal that proves ancient humans and Neanderthals didn't just meet - they had families together! 👨👩👧👦 This discovery shows that many people today have both human and Neanderthal ancestors, making our family tree 🌳 much more interesting than we once thought. The child was buried with special items and colors 🎨, showing that their community cared deeply about them 💝, even though they were different from others. 🤗

🗝️ Takeaways

🔍 Lapedo Child lived 28,000 years ago, showing Neanderthal traits long after their supposed extinction

🧬 Non-African humans carry 2-4% Neanderthal DNA

🤝 Interbreeding between humans and Neanderthals was common, not rare

⚰️ Elaborate burial suggests hybrid children were valued community members

🧪 Neanderthal genes influence modern traits like immunity and pain sensitivity

🌍 Human evolution was more complex than previously thought

The Lapedo Child: When Our Family Tree Got a Lot More Complicated

"Evolution is just a theory," says every science-denier who's never bothered to look at the mountains of evidence staring them in the face. Well, here's one more fossil to add to that mountain, and it's a doozy.

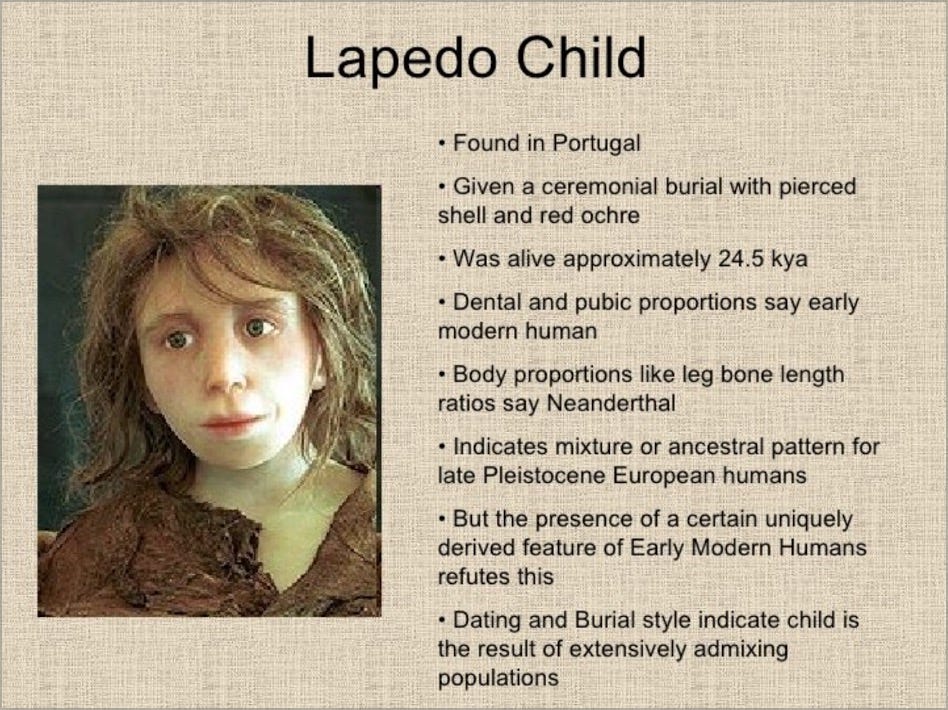

Meet the Kid Who Rewrote Our Evolutionary Story

In December 1998, while many of us were worrying about Y2K and whether our computers would implode at midnight on New Year's Eve, archaeologists in Portugal's Lapedo Valley were making a discovery that would genuinely flip the script on human evolution. No computer meltdown required.

They found the nearly complete skeleton of a child, about 4 years old at death, carefully buried in a rock shelter. At first glance, it seemed like just another Paleolithic human child—interesting, sure, but not revolutionary.

But then the scientists took a closer look.

This kid was... different. The skeleton showed a peculiar mix of features: some distinctly Homo sapiens (like us modern humans), and others unmistakably Neanderthal. It was as if someone had taken parts from Column A and parts from Column B and assembled a prehistoric hybrid.

Ladies and gentlemen, meet the Lapedo Child—the kid who would launch a thousand scientific papers.

Why Scientists Lost Their Collective Minds Over This Discovery

So what exactly makes this tiny skeleton such a big deal? Let's break it down:

The Dating Game: Using the latest fancy-pants technique called hydroxyproline dating (think of it as carbon dating's more meticulous, OCD cousin), scientists have now confirmed the child lived between 27,780 and 28,850 years ago.

The Timing Problem: Here's where things get weird. Neanderthals supposedly went extinct around 40,000 years ago. This kid lived roughly 12,000 years AFTER that extinction event. Awkward.

The Physical Evidence: The Lapedo Child sports a distinctly modern human chin and skull, but has shorter limbs and other bodily proportions that scream "Neanderthal" louder than a caveman discovering fire.

This wasn't just a case of a few Neanderthal genes lingering in the gene pool like that weird uncle nobody talks about at family reunions. This was substantial enough to create visible, measurable anatomical features thousands of years after Neanderthals supposedly packed their evolutionary bags.

In scientific terms, this was the equivalent of finding Elvis working at a 7-Eleven in 2025.

How This Changes Our Human Origin Story

For decades, the dominant narrative about human evolution went something like this: Modern humans evolved in Africa, spread out across the globe, encountered other hominid species like Neanderthals, and promptly replaced them—either through competition, conflict, or simply being better adapted to survive.

It was a clean, linear story. Homo sapiens: 1, Everyone else: 0.

The Lapedo Child takes that neat narrative and tosses it into the evolutionary garbage bin.

What we're seeing instead is a much messier, more complex scenario:

Humans and Neanderthals didn't just pass each other in the prehistoric night—they got cozy. Very cozy.

This interbreeding wasn't just a rare one-off event, but likely common enough that distinctive Neanderthal features persisted visibly for 10,000+ years.

The "replacement" model of human evolution is too simplistic. We didn't replace Neanderthals; in many ways, we absorbed them.

As João Zilhão, one of the original discoverers of the Lapedo Child, put it: "For diagnostic Neanderthal features to have persisted for so long, after thousands of years in this population, it had to be the case that admixture between both groups had been extensive—i.e., the rule and not the exception."

Translation: Our ancestors got busy with Neanderthals. A lot.

The Ritual Burial: Not Just Any Hole in the Ground

Another fascinating aspect of the Lapedo Child discovery is the burial itself. This wasn't a haphazard disposal of remains but a carefully executed ritual:

The body was covered with red ochre (an iron oxide pigment used extensively in prehistoric rituals)

A rabbit was placed on top of the shrouded body, also stained with red ochre

Shell ornaments were included in the grave

Deer bones appear to have been used to position the body

This elaborate burial tells us something important: whoever this child was, they were valued by their community. This wasn't an outcast or a rejected hybrid—this was a loved member of their group.

Even more intriguing is what happened next: the site was abandoned for more than 2,000 years after the burial. As Zilhão suggests, "Perhaps the death event resulted in the site becoming taboo, and a social rule to avoid it was put in place until the memory of the event faded away."

Imagine a place so sacred or so tragic that humans avoided it for two millennia. Talk about leaving an impression.

The Broader Picture: Neanderthals in Our DNA

The Lapedo Child isn't the only evidence of human-Neanderthal hanky-panky. In 2010, scientists successfully sequenced the Neanderthal genome, opening the floodgates to a new understanding of our relationship with our extinct cousins.

The results? Every person with ancestry from outside of Africa carries approximately 2-4% Neanderthal DNA in their genome. Yes, that means you (unless you have purely African ancestry).

Some of these Neanderthal gene variants influence traits like:

Skin and hair color

Immune response

Fat metabolism

Risk for certain diseases

Pain sensitivity

Mood disorders

So not only did our ancestors interbreed with Neanderthals, but we're still carrying the genetic souvenirs of those prehistoric encounters. That weird cowlick you can't control? Blame your Neanderthal great-great-great-(add a few thousand more "greats")-grandparent.

Other Hybrid Humans: The Lapedo Child Isn't Alone

Since the Lapedo Child discovery, other finds have supported the hybridization theory:

Oase 1: A 40,000-year-old jawbone found in Romania shows a similar mix of features and contains 6-9% Neanderthal DNA—evidence of a Neanderthal ancestor within 4-6 generations.

Vindija Cave Remains: Specimens from Croatia have yielded Neanderthal DNA that helped confirm interbreeding.

Denisovans: Another extinct human species discovered in Siberia also interbred with modern humans. Many people from East Asia and Oceania carry Denisovan DNA alongside their Neanderthal genes.

The Denny Hybrid: A bone fragment found in Denisova Cave belonged to a teenage girl with a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father—direct evidence of interbreeding between these two extinct human species.

It seems our family tree is less a tree and more a tangled bush with branches wrapping around each other in ways that would make a botanist blush.

What This Means for You, the Modern Human Reading This

So you've got Neanderthal DNA. What does that mean for your life, beyond being an excellent conversation starter at particularly nerdy cocktail parties?

For one thing, it means human evolution wasn't the simple march of progress depicted in those familiar illustrations of an ape gradually standing upright and turning into a modern human. It was a complex web of interactions, migrations, adaptations, and yes, interbreeding.

But it also means something more profound: diversity in our species isn't new, and it isn't something to fear. Humans have been mixing and matching genes with other human groups since before we were even fully "modern." Genetic diversity has been our superpower, not our weakness.

Those Neanderthal genes you're carrying? They may have helped your ancestors survive in colder climates, fight off certain pathogens, or adapt to new environments. When different human groups met and mixed, the resulting hybrid vigor often created more resilient populations.

If anything, the Lapedo Child reminds us that "purity" is a myth, and that our strength as a species has always come from our ability to adapt, intermingle, and incorporate beneficial traits from diverse sources.

The Burial Site's Taboo: A Cultural Connection

One of the most intriguing aspects of the new dating of the Lapedo Child is the evidence that after the burial, humans abandoned the site for more than two millennia. Researchers speculate that the child's death may have triggered a cultural taboo around the location.

This suggests something remarkably human: a capacity for cultural memory and symbolic thinking that could persist across generations. These weren't just proto-humans grunting and dragging knuckles (despite what certain politicians might lead you to believe about their opponents). These were people with complex cultural systems, rituals, and beliefs.

The fact that this taboo applied to a child with mixed Neanderthal-human heritage further suggests that these hybrid individuals weren't marginalized but were integrated members of their communities, worthy of elaborate burial rituals and culturally significant remembrance.

What Comes Next: The Future of Paleogenetics

The story of human evolution continues to evolve itself, thanks to advancing technology and new discoveries. Here's what's on the horizon:

Improved Dating Techniques: The hydroxyproline method used to date the Lapedo Child more precisely represents just one advancement in our ability to determine the age of ancient remains.

Ancient DNA Extraction: Scientists continue to refine methods for extracting and analyzing DNA from increasingly older and more degraded samples.

Population Genetics: More sophisticated computer models are helping us understand complex population movements and interbreeding events.

Paleoproteomics: Analysis of ancient proteins may soon provide information from specimens too old for DNA analysis.

Microbiome Studies: Examining the ancient bacteria and other microorganisms associated with human remains could reveal new insights about health, diet, and lifestyle.

If you're fascinated by this subject (and really, how could you not be?), there are plenty of ways to learn more:

Visit natural history museums with human evolution exhibits

Follow paleoanthropologists like João Zilhão, Chris Stringer, and Svante Pääbo on social media

Read popular science books like "Sapiens" by Yuval Noah Harari or "Who We Are and How We Got Here" by David Reich

Support organizations dedicated to human origins research

The journey to understand our origins is ongoing, and each discovery like the Lapedo Child adds another piece to the magnificent puzzle of human evolution.

And just think—the next major discovery that rewrites our understanding of human evolution might be sitting in a museum drawer right now, misclassified and waiting for someone to take a second look, or buried under a parking lot somewhere, waiting to be found.

What do you think?

Has this changed how you view human evolution? Do you see our relationship with Neanderthals differently now? Drop a comment below and let me know:

If you could meet the Lapedo Child's parents, what would you ask them about life in prehistoric Iberia?

Which aspect of Neanderthal genetics do you find most surprising—their contribution to our immune system, pain perception, or something else entirely?

Stay curious, fellow hybrid humans!

I have read about attempts to resurrect various extinct species, most spectacularly, the mammoth. Of course, comparable resurrection of the Neanderthals -- whose embryos would need to be carried by human females -- would never transcend ethical concerns, but who knows what we might learn. Meanwhile, I am sketching a novella in which the Neanderthal genome figures prominently. [Of course, this will be a work of fiction...]